-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Expertise

Publication

Florida Property Tort Reforms – Evolving Conditions

Publication

Is Human Trafficking the Next Big Liability Exposure for Insurers?

Publication

When Likes Turn to Lawsuits – Social Media Addiction and the Insurance Fallout

Publication

Generative Artificial Intelligence and Its Implications for Weather and Climate Risk Management in Insurance

Publication

Engineered Stone – A Real Emergence of Silicosis

Publication

Who’s Really Behind That Lawsuit? – Claims Handling Challenges From Third-Party Litigation Funding -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Publication

Understanding Physician Contracts When Underwriting Disability Insurance

Publication

Voice Analytics – Insurance Industry Applications [Webinar]

Publication

GLP-1 Receptor Agonists – From Evolution to Revolution U.S. Industry Events

U.S. Industry Events

Publication

Always On: Understanding New Age Addictions and Their Implications for Disability Insurance

Publication

Dying Gracefully – Legal, Ethical, and Insurance Perspectives on Medical Assistance in Dying -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

Assessing Terminal Illness Claims – How Inaccurate Survival Estimates Present a Challenge

June 27, 2017

Mary Enslin

English

Advances in medicine and public health improvements have dramatically altered not only how people live but also how they die, leading to increases in life expectancy in most parts of the world. We can predict a dramatic rise in the numbers of people living with a terminal illness. For some, death is no longer a sudden event but rather a “long, slow fade,” as Atul Gawande puts it in his book, Being Mortal.

Unfortunately, most public health systems are unprepared to cope with the needs of an ageing population. For instance, while 44% of adults in the UK have multiple long-term health conditions in the final year of life, only 30% receive adequate care.1 Meanwhile, much younger people who receive a terminal diagnosis also face disruption and uncertainty.

Terminal Illness (TI) is a supplementary rider to a Life policy that acts to accelerate the death benefit when a policyholder is diagnosed and allows him or her to access a portion, or the entire value, in the period before they die. The proceeds may be used for any purpose, including access to treatment or palliative care.

Riders like this have been offered by insurers since the late 1980s, usually at no additional cost.2 They have become more popular in recent years and claims volumes have risen in some markets, most likely due to increased awareness of the rider.

We tend to think of “terminal illness” as giving no hope of prolonged survival. Certainly doctors reserve the term to describe progressive incurable diseases that they expect to be fatal soon – an inoperable tumour, for example. Indeed, cancers account for most terminal diagnoses. Others arise from progressive (non-malignant) diseases of the circulatory, respiratory or nervous systems; infectious diseases such as HIV; and hereditary conditions, including muscular dystrophy and cystic fibrosis.

However, a diagnosis of any one of these doesn’t automatically mean that death is imminent. Advances in medical treatment mean patients may experience that long, slow fade. It is uncertainty about “how long” the patient could live that creates a difficulty for TI claims assessors.

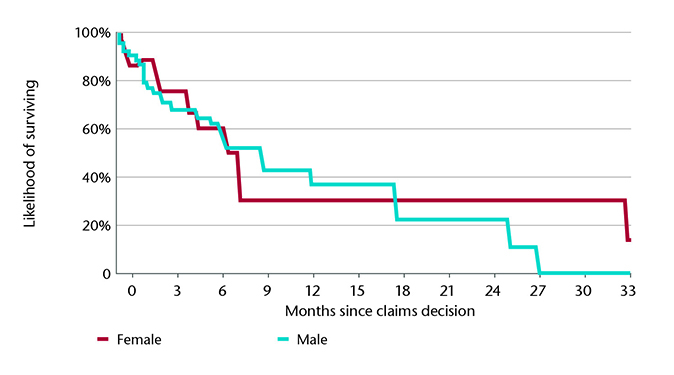

Survival Rates for Admitted TI Claims in South Africa3

As a result, insurers’ TI definitions are conditional on the expectation of death occurring within 12 months of a diagnosis (24 months in some markets). Insurers generally make TI claims conditional on this prognosis being confirmed by their own Chief Medical Officer or an independent medical specialist.

However, doctors have found that three months seems to be the duration against which they can predict survival with a degree of certainty, according to studies evaluating survival estimations. Consequently, the insurance industry’s definition may be difficult to apply in a clinical setting.

Doctors may turn to median survival statistics for guidance. However, these statistics are not always a reliable indicator of an individual’s prognosis as each patient has unique circumstances and responds to the illness and treatment in his or her own way. The lack of local or country-specific research, and the use of old data and survival rates that often include very early and late diagnoses, could also make it difficult to predict life expectancy.

It is possible that some doctors overstate life expectancy or avoid discussing it to shield patients from the grim reality of a terminal prognosis. Unsurprisingly, most choose to focus on treatment options, success rates and action plans or anything that can support the patient’s resolve, with the result that a doctor’s prediction is more likely to be overly optimistic.

The inaccuracy of survival estimates, in combination with the potential reputational risk of declining a claim, presents a real challenge for claims assessors. As the popularity of the TI rider grows, insurers should consider how they meet this demand while bearing treatment advances and the medical community’s definitions in mind.

Endnotes

- www.mariecurie.org.uk/globalassets/media/documents/policy/campaigns/changing-the-conversation-report.pdf.

- The TI Benefit Rider has been offered in Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, the UK and U.S. where conditions vary depending on the state.

- Survival rates were calculated by analysing South African claims data regarding admitted terminal illness claims against the South African national death registry. This was necessary in order to compare the predicted date of death with the actual date of death.