-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Expertise

Publication

60, 30, 15, … 7.5? What History Suggests About Generative AI

Publication

AI Agent Potential – How Orchestration and Contextual Foundations Can Reshape (Re)Insurance Workflows

Publication

Creating Strong Reinsurance Submissions That Drive Better Outcomes

Publication

Is Human Trafficking the Next Big Liability Exposure for Insurers?

Publication

Engineered Stone – A Real Emergence of Silicosis -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

Gen Re’s valuable insights and risk transfer solutions help clients improve their business results. With tailor-made reinsurance programs, clients can achieve their life & health risk management objectives.

UnderwritingTraining & Education

Publication

Diabetes and Critical Illness Insurance – Bridging the Protection Gap

Publication

Underwriting the Dead? How Smartphones Will Change Outcomes After Sudden Cardiac Arrest

Publication

Always On: Understanding New Age Addictions and Their Implications for Disability Insurance

Publication

Dying Gracefully – Legal, Ethical, and Insurance Perspectives on Medical Assistance in Dying

Publication

AI Agent Potential – How Orchestration and Contextual Foundations Can Reshape (Re)Insurance Workflows Business School

Business School -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

Underwriting the Dead? How Smartphones Will Change Outcomes After Sudden Cardiac Arrest

October 16, 2025

Dr. Maximilian Kanzler

English

Every year, on 16 October, the “World Restart a Heart Day” draws global attention to resuscitation after sudden cardiac arrest. For life and health insurers, this is not “just” a medical topic. The real question is: will new rescue concepts enable more people to survive a cardiac arrest with a good prognosis? And should these survivors be assessed differently in underwriting?

The Critical Factor: Time Without Blood Flow

A cardiac arrest means the heart suddenly stops beating. From that moment on, the brain and other vital organs are no longer supplied with oxygen. Within three to five minutes, the cells of the brain begin to die irreversibly. In medical language, this period is called “no‑flow time”: the time span when no chest compressions are being performed and the body’s own circulation has not yet been restored by defibrillation. The longer this phase lasts, the lower the chances of survival. And here, literally every minute counts.1

International data show that after a cardiac arrest outside a hospital (OHCA – out-of-hospital cardiac arrest), on average only about 10% of patients are ultimately discharged alive after the subsequent in‑hospital care.2,3 By contrast, for a cardiac arrest occurring inside a hospital (IHCA – in‑hospital cardiac arrest) where professional help is immediately available and no‑flow time is typically very short, the survival rate is about twice as high, at about 20% to 25%.4,5 These figures strongly illustrate how essential a minimal no‑flow time is and how powerful immediate professional resuscitation is compared to bystander-only resuscitation.

Equally striking is the inverse approach to the numbers: for each minute of cardiac arrest without chest compression, the chance of survival drops by an astonishing 10% per minute passed.6 Against this backdrop, it becomes clear that rapid restoration of circulation is decisive for improving survival.

Progress to Date – With Limits

Precisely for these reasons, the emergency chain of response has evolved over recent decades. After an emergency call, a dispatcher-guided bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) until the emergency medical services (EMS) vehicle arrives at scene is now standard in nearly all dispatch facilities around the world, and the spread of automated external defibrillators (AEDs), defibrillators specifically designed for use by laypeople, has structurally improved the odds.

And yet: in many countries only a fraction of bystanders actually begin chest compression. In Germany for example, the bystander-CPR rate is about 40% to 45%, while in Scandinavian countries such as Norway or Sweden it reaches up to 70%.7,8 These differences reflect the success of long-standing public campaigns in Northern Europe, while in Central Europe and other parts of the world inhibition to act persists in the public mind.

AED use lags far behind its potential. Even in countries with dense public availability – such as the United States – AEDs are applied in fewer than 20% of eligible out-of-hospital emergency cases.9 This is a disappointing outcome, considering that early defibrillation is a key factor for better survival.

Despite concerted efforts to adapt the emergency chain of response, a lethal gap remains between the event of cardiac arrest and professional care by emergency medical services – and it is precisely this gap that the new systems addresses.

The Game-changer: Smartphone-based First Responder Systems

In a growing number of countries, medically qualified first responders – physicians, nurses, EMS professionals and in some systems laypeople specifically trained in chest compression – are alerted by smartphone app when a cardiac arrest is reported in their immediate geographic vicinity. Thanks to modern localization technology on their personal smartphones, these responders on average can reach the emergency scene significantly faster than EMS. The goal is obvious: to shorten the critical no‑flow time as much as possible.

Internationally, a growing landscape of such systems exists. In Sweden, the “SMS-Lifesaver” program was launched as early as 2012. A randomized study showed that phone-based alerting significantly increased the rate of chest compression.10 Denmark followed and established “Hjerteløber” (“heart-runner”) on a large scale, with high participation, resulting in app-alerted responders often arriving before EMS and markedly increasing the chance of early defibrillation.11

In the United Kingdom, “GoodSAM” was integrated into ambulance dispatch centers, with a focus more towards medically trained responders.12 In Switzerland, local first responder networks could document real-time gains and high feasibility of their system,13 while in the U.S., “PulsePoint” is a widespread application. Depending on the region, in addition to professional off-duty responders, CPR-trained citizens are included, so it’s a mixed system adapted to geographic challenges of the U.S. between densely populated areas and the vast countryside. Ongoing studies are evaluating its utility and implementation in North America.14

Germany is also an active market with multiple initiatives. Programs such as “Mobile Retter” (“mobile rescuers”) and “Region der Lebensretter” (“region of lifesavers”) deliberately rely on medically trained responders who are alerted by the dispatch centers in parallel with EMS. Prospective companion studies such as HEROES15 and REAP16 are under way to quantify effects on survival and neurological outcome under real-life and systemically monitored conditions. Based on early study results, the alerting algorithm was refined to further reduce time to chest compression and to increase AED use. It now alerts not only one but up to four responders simultaneously and assigns algorithm-based roles for the early resuscitation phase to each one of those.

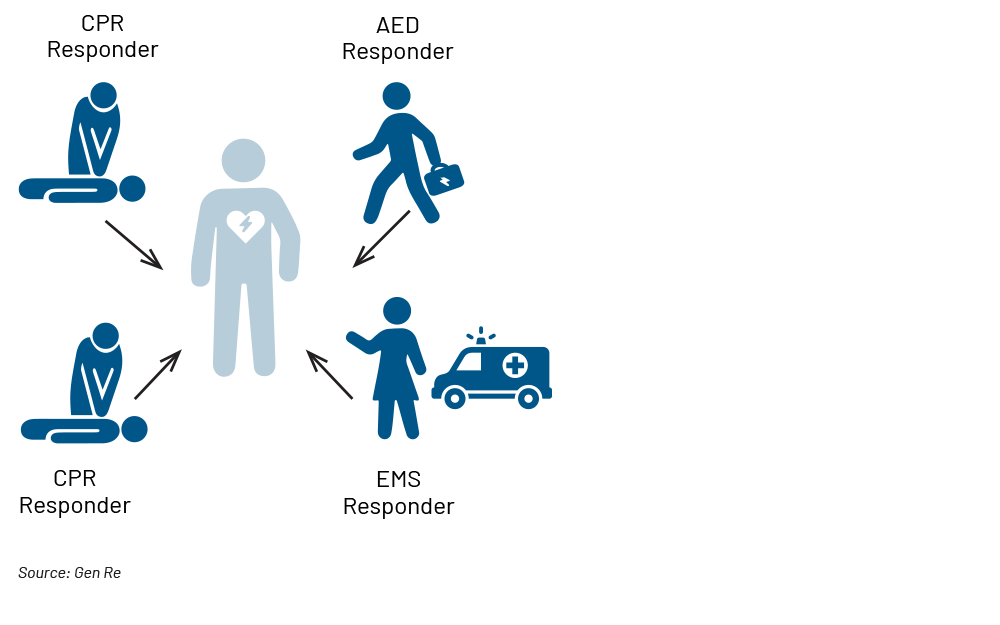

Third-generation First Responder App With Role Assignment

Four responders are app-alerted. The two responders predicted by the algorithm to arrive first are routed directly to the patient for immediate CPR. If none of those responders has indicated carrying an AED, the third responder is routed to the nearest AED and brings it to the scene. The fourth responder guides EMS to the location.

Evidence: Shorter No‑flow Time, Better Outcomes

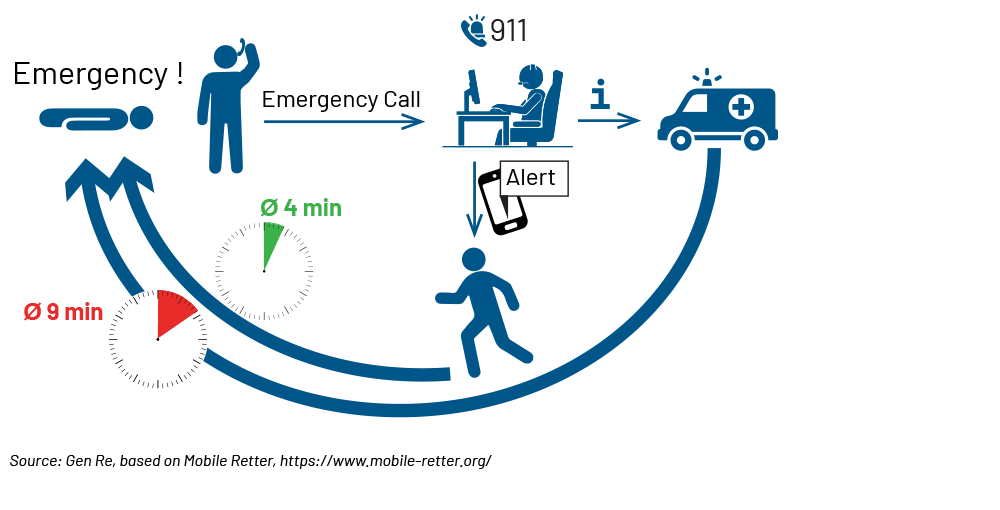

Analyses from several countries consistently show that app-alerted responders reach the patient about four to five minutes after the emergency call – significantly earlier than EMS, which on average arrives after eight to 12 minutes.17,18,19 This time advantage effectively halves the no‑flow time and creates the crucial foundation for better clinical results.

A 50% Time Gain Through App-based First Responder Alerting

Classic emergency chain of response vs. chain of response with app-alerted responders: EMS arrival within eight to 12 minutes vs. app-alerted first responder arrival of four to five minutes.

International meta-analyses report that regions with active first responder systems achieve a ~20% to 30% higher 30‑day survival compared with regions without such structures.20 Crucially, it is not only short-term survival that improves but, above all, functional outcome. Studies show that patients who receive early chest compression and an early defibrillation are more frequently discharged with a good neurological outcome (cerebral performance category [CPC] scale 1–2). This group has substantially better one-year survival, and long-term studies indicate that the quality of life and morbidity of these survivors is often comparable to that of the general population.21,22

The trend is clear: the shorter the no‑flow time, the better the chances of survival and long-term functional outcomes.

What This Means for the Insurance Industry

Traditionally, the insurance industry has taken a mostly binary view: “History of cardiac arrest = decline.” Early mortality seemed too high, neurological prognosis too uncertain, the underlying disease risk too great and detailed work‑up non-efficient or even impossible.

The new first responder apps incorporate the ability to change this perspective: in future, structured data from the decisive early CPR phase – previously hidden in a kind of black hole – will be available. Through first responder apps and their prospective companion studies, it becomes possible to obtain a fingerprint of the early decisive phase of a resuscitation, at a level of detail previously unheard of: the time to first compression; whether an AED was used in time; whether a qualified responder was involved; the initial rhythm of the heart; and whether the arrest was witnessed or unwitnessed. These key variables are strong prognostic markers that previously could be reconstructed only with arduous effort in study populations – but which these new systems will document at scale.

This opens the perspective to move towards a differentiated risk assessment in the foreseeable future. Insurers may identify subgroups for whom – despite a survived cardiac arrest – a favorable long-term prognosis is realistic: for example, younger applicants with a clear and manageable cause of cardiac arrest and, at the same time, a short no‑flow time, early defibrillation, good neurological outcome (CPC 1–2) and stable cardiac function. For such profiles, insurability may be possible in the future.

In the long term, regional factors may also play a role: if these initiatives become standard care, which they probably will, those living or working in regions with dense coverage of qualified first responders have better odds in an emergency. This suggests that risk assessment will become increasingly more data-driven at a pre-individualized processing level.

The insurance industry may consider not only reacting to these changes but also helping to shape them proactively. Investing in prevention – from AED programs and CPR training up to supporting local first responder networks – delivers tangible social impact and may even reduce risk in existing portfolios through improved mortality and morbidity in CPR scenarios.

Outlook

Smartphone-based first responder systems address one of the emergency chain of response’s greatest weaknesses: deadly no‑flow time. Everyday standard personal smartphones are enabling a monumental leap forward in emergency medicine by using them in a new, creative and meaningful way.

For the insurance industry, this means that in future, significantly more people will survive a cardiac arrest – possibly twice to three times as many as today based on current data. A growing proportion of survivors will be discharged with good functional outcomes. Consequently, it is to be expected that a larger share of these survivors will feel subjectively healthy – probably because they actually are – and will therefore increasingly seek Life or Disability insurance products.

Large, ongoing, prospective studies offer hope that context and data-based decision-making will enable access to this previously untouched customer segment.

- Olasveengen, T.M., Mancini, M.E., Maconochie, I.K., et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines 2021: Basic Life Support. Resuscitation. 2021;161:115–151. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.02.009, https://cprguidelines.eu/assets/guidelines/European-Resuscitation-Council-Guidelines-2021-Ba.pdf

- American Heart Association. CPR Facts & Stats. Web resource, continuously updated (factsheet), https://cpr.heart.org/en/resources/cpr-facts-and-stats

- Wnent, J., Müller, M.P., Gräsner, J.T., et al. The German Resuscitation Registry – Epidemiological data for out-of-hospital and in‑hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation Plus. 2024;18:100427. doi:10.1016/j.resplu.2024.100427, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38646091/

- Nallamothu, B.K., Greif, R., Anderson, T., et al. Ten Steps Toward Improving In‑Hospital Cardiac Arrest Quality of Care and Outcomes. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. 2023;16(11):e010491. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.123.010491, https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.123.010491

- Scquizzato, T., Gamberini, L., D’Arrigo, S., et al.; Collaborators. Incidence, characteristics, and outcome of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in Italy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Resuscitation Plus. 2022 Nov 11;12:100329. doi: 10.1016/j.resplu.2022.100329. PMID: 36386770; PMCID: PMC9663528, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9663528/

- Ibid. See endnote 1.

- Gräsner, J.T., Wnent, J., Herlitz, J. et al. Survival after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in Europe – Results of the EuReCa TWO study. Resuscitation. 2020;148:218–226. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2019.12.042, https://europepmc.org/article/med/32027980

- Wissenberg, M., Lippert, F.K., Folke, F., et al. Association of National Initiatives to Improve Cardiac Arrest Management With Rates of Bystander Intervention and Patient Survival After Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. JAMA. 2013;310(13):1377–1384. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.278483, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24084923/

- Ibid. See endnote 2.

- Ringh, M., Rosenqvist, M., Hollenberg, J., et al. Mobile-Phone Dispatch of Laypersons for CPR in Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;372:2316–2325. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1406038, https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1406038

- Andelius, L., Malta Hansen, C., Lippert, F.K., et al. Smartphone Activation of Citizen Responders to Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2020;76(1):43–53. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.073, https://www.jacc.org/doi/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.073

- Smith, C.M., Lall, R., Fothergill, R.T., et al. The effect of the GoodSAM volunteer first responder app on survival to hospital discharge following out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. European Heart Journal – Acute Cardiovascular Care. 2022;11(1):20–31. doi:10.1093/ehjacc/zuab103, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8757292/

- Lay persons alerted by mobile application system initiate earlier cardio-pulmonary resuscitation: A comparison with SMS-based system notification Caputo, Maria Luce et al., https://www.resuscitationjournal.com/article/S0300-9572(17)30103-X/fulltext

- PulsePoint Foundation. PulsePoint Program Overview. Program website (U.S. mixed-responder model), https://www.pulsepoint.org/

- Müller, MP., Ganter, J., Busch, HJ., et al.; HEROES Investigators. Out-of-Hospital cardiac arrest & SmartphonE RespOndErS trial (HEROES Trial): Methodology and study protocol of a pre-post-design trial of the effect of implementing a smartphone alerting system on survival in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation Plus. 2024 Feb 1;17:100564, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10847368/

- German Clinical Trial Register – REAP-Studie, https://drks.de/search/de/trial/DRKS00031349/details and/or https://mobile-retter-regensburg.de/reap-studie/

- Ringh, M., Rosenqvist, M., Hollenberg, J., et al. Mobile-Phone Dispatch of Laypersons for CPR in Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;372:2316–2325. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1406038, https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1406038

- Andelius, L., Malta Hansen, C., Lippert, F.K., et al. Smartphone Activation of Citizen Responders to Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2020;76(1):43–53. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.073, https://www.jacc.org/doi/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.073

- Local lay rescuers with AEDs, alerted by text messages, contribute to early defibrillation in a Dutch out-of-hospital cardiac arrest dispatch system. Zijlstra, Jolande A. et al., Resuscitation, Volume 85, Issue 11, 1444–1449, https://www.resuscitationjournal.com/article/S0300-9572(14)00686-8/abstract

- Jonsson, M., Kluger, M.T., Berglund, E., et al. Dispatch of Volunteer Responders to Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2023;82(2):124–136. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2023.05.017, https://www.jacc.org/doi/10.1016/j.jacc.2023.05.017

- Sandroni, C., D’Arrigo, S., Cacciola, S., et al. Prognostication after cardiac arrest. Critical Care. 2018;22:150. doi:10.1186/s13054-018-2060-7, https://ccforum.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13054-018-2060-7

- Nolan, J.P., Sandroni, C., Böttiger, B.W., et al. European Resuscitation Council and ESICM Guidelines 2021: Post-resuscitation care. Resuscitation. 2021;161:220–269. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.02.012, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7993077/

All endnotes last accessed on 28 September 2025.