-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Trending Topics

Publication

60, 30, 15, … 7.5? What History Suggests About Generative AI

Publication

Creating Strong Reinsurance Submissions That Drive Better Outcomes

Publication

Florida Property Tort Reforms – Evolving Conditions

Publication

Is Human Trafficking the Next Big Liability Exposure for Insurers?

Publication

Generative Artificial Intelligence and Its Implications for Weather and Climate Risk Management in Insurance -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Training & Education

Publication

AI Agent Potential – How Orchestration and Contextual Foundations Can Reshape (Re)Insurance Workflows

Publication

Diabetes and Critical Illness Insurance – Bridging the Protection Gap

Publication

Group Medical EOI Underwriting – Snapshot of U.S. Benchmark Survey

Publication

Why HIV Progress Matters

Publication

Dying Gracefully – Legal, Ethical, and Insurance Perspectives on Medical Assistance in Dying Moving The Dial On Mental Health

Moving The Dial On Mental Health -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

Is Human Trafficking the Next Big Liability Exposure for Insurers?

September 22, 2025

Matt Burns,

Tim Fletcher

Region: North America

English

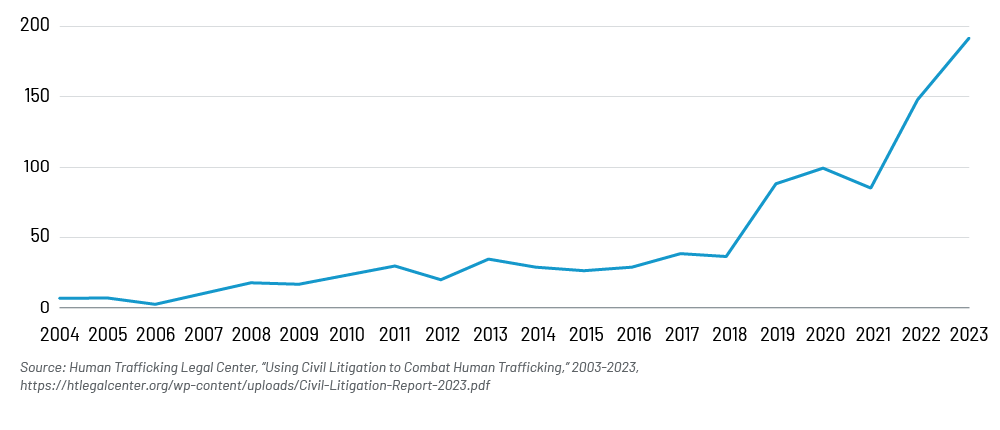

Human trafficking is a very real and potentially costly exposure, with the number of civil claims and lawsuits rising steeply over the last five years. This trend has caught the attention of high-profile plaintiff legal firms, especially in cases where there is a large corporation or franchisor involved. It’s becoming a hot topic for the plaintiffs’ bar in this segment because of the high limits involved, and yet it is not even registering on the list of emerging risks for many insurers.

Recent events have further brightened the spotlight, as seen in the recent and extensively covered Sean “Diddy” Combs trial on charges that included sex trafficking and resulted in convictions on lesser charges of transporting prostitutes.1 As Mr. Combs awaits sentencing on those charges, he also faces more than 50 civil suits that accuse him of sexual abuse, with most pending in New York and involving accusations extending as far back as the 1990s.2 In another example, the Jeffrey Epstein saga resulted in his 2019 indictment on sex trafficking charges and continues today with renewed attention on his longtime companion Ghislane Maxwell, who is currently serving a 20‑year sentence for sexually abusing and exploiting teenage girls.3

Human trafficking and modern slavery, according to the U.S. State Department, are umbrella terms often used interchangeably “to refer to a crime whereby criminals exploit and profit at the expense of adults or children by compelling them to perform labor or a commercial sex act. When a person younger than 18 is involved, it’s a crime irrespective of whether there is any force, fraud, or coercion involved.”4

While sex trafficking in the hospitality sector (e.g., hotels) is a common form of human trafficking, it can also be seen in industries that depend on low-cost labor.5 Agriculture is a seemingly obvious risk sector, but human trafficking can also exist in domestic service, construction and factory work, as well as in beauty and healthcare businesses, for example.6

Human Trafficking – Large-Scale Criminal Enterprise

- 24.9 million people worldwide are subjected to sex trafficking7

- 11,999 sex trafficking cases identified in 20248

- Sex and labor trafficking reportedly a $150 billion criminal enterprise worldwide, with two-thirds estimated to be from sex trafficking9

- In 2024, there were 601 cases linked to hotels10

- Occurs in major cities (Atlanta, Philadelphia, Charlotte, Dallas, Columbus, Seattle)

Civil Suits Filed under the Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act (TVPRA) [2003–2023]

Hotels, Sex Trafficking, and the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA)

In the U.S., prohibitions against human trafficking are rooted in the 13th amendment to the Constitution, which was ratified in 1865 and barred slavery and involuntary servitude.11 Driven by compelling examples of human trafficking during the late 20th century, in 2000 Congress passed comprehensive legislation to fight human trafficking called the Trafficking Victim Protection Act of 2000 (TVPA), and in 2023 passed the Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2023 (TVPRA).12 Under the TVPRA, victims can seek civil remedies against human traffickers.13 Further, while most states ban prostitution, the TVPA and TVPRA do not make criminal the voluntary exchange of sexual activities for money; they instead target those who force victims into selling themselves, as well as any third party that knowingly realizes a financial windfall.14

Hotels have proven to be fertile ground for sex trafficking prosecutions, with “nearly half of all sex trafficking cases brought under the TVPRA since 2009 targeting hotels and the hospitality industry for ’financially benefitting’ from sex trafficking.”15

The allegations arising from hotel-related sex trafficking are both heartbreaking and far too common. The National Human Trafficking Hotline identified 11,999 human trafficking cases in 2024 involving 21,865 victims.16 Additionally, it identified specific instances of sex trafficking taking place at 601 hotels across the U.S.17 The Hotline reported the involvement of 2,666 minors (compared to 8,233 adults) and 8,359 females (compared to 1,972 males).18

Lawsuit activity extends countrywide, with a growing number of cases brought by survivors against hotels and motels for allegedly facilitating their exploitation under the TVPA and the TVPRA.19 Significant awards and settlements have resulted, such as a 2023 case in which eight plaintiffs received a $24 million settlement over allegations that the owners of a Philadelphia Days Inn ignored signs that they were being sexually trafficked at the facility. The suit also alleged the hotel was negligent when they hired a convicted felon to work as a security guard. The guard, among others, was ultimately prosecuted for being involved in the trafficking operation.20 That same year, three women who were trafficked as minors in another Philadelphia hotel received a $37.5 million arbitration award for claims that they were lured in 2012 through social media by a man who masqueraded as a woman with a money-making opportunity, then manipulated the women mentally and threatened them physically during a four-month period at the hotel.21

Recent cases in Georgia have generated headlines and further heightened public awareness. In July, an Atlanta-based hotel, facing claims that it left unchecked a sex trafficking operation over an extended period, reached a $6 million settlement days prior to trial.22 In that case, the plaintiff claimed the signs of illegal activity were rampant and obvious, with sex workers and clients frequently loitering on premises, numerous online reviews mentioning prostitution, and a string of police operations targeting that activity at the hotel.23 Just days before that, a DeKalb county jury awarded $40 million to a woman who said she had been sexually trafficked as a teenager, resulting in what was believed to be Georgia’s first successful sex-trafficking verdict against a hotel operator.24 Plaintiff’s counsel further contended afterward that the verdict (of which $30 million were in punitive damages) represented the “largest sex trafficking verdict in U.S. history against a hotel.”25

Coverage Concerns

At first glance, the exposures arising from human trafficking are seemingly outside of CGL coverage, considering that these activities are intentional, involve illegal activity, and are potentially excluded by clearly defined and longstanding exclusions that include assault and battery, intentional acts, criminal acts, and newer specific exclusions for sexual abuse and molestation as well as human trafficking. While ISO has had in place an array of abuse and molestation exclusions for a number of years, it is now also filing a comprehensive human trafficking exclusion, with an expected effective date of January 1, 2026. In the interim, a number of human trafficking exclusions are in use. While E&S markets may have been the first to introduce policy level exclusions, many standard carriers drafted their own exclusions.

Whether the human trafficking exclusion will succeed remains an open question. However, what is all but certain is the need for its existence, at least based on what has been seen to date as to exclusions for sexual abuse and molestation, as applied to the ever-growing body of case law surrounding hotel sex-trafficking. As has been seen in cases that involve contested coverage, courts will in some instances scrutinize complaints for allegations that trigger coverage, while plaintiff attorneys will draft those complaints with that reality in mind. For example, in the above-mentioned case that resulted in the $40 million verdict, the hotel’s insurer filed a declaratory judgment action based on policy exclusions for abuse and molestation. In September, a Georgia federal court ruled that the carrier must defend the insured, ruling that the exclusions did not apply because the plaintiff alleged in her underlying suit that she suffered bodily injury independent of any alleged abuse and molestation, leaving for further determination as to whether it must indemnify the insured.26

Underwriting Considerations – Hotels/Motels

With growing public awareness of human trafficking and the ongoing uncertainty associated with court interpretations of abuse and molestation exclusions, it’s important for insurers to scrutinize any risk that carries even a theoretical potential for human trafficking.

How should an underwriter approach this exposure, particularly when there is a level of criminal activity involved? Much of the following is consistent with a standard risk assessment, however, when evaluating the potential for human trafficking exposure we recommend careful consideration of factors that may not be evident in a standard application.

The Producer

Does your agent/broker control the account? Do they have a history with and/or knowledge of the insured and the specific location? Has coverage been consistent, uninterrupted, and not pending possible cancellation? Are up‑to-date carrier loss runs available for a minimum of five years? Have prior carriers inspected the location(s) resulting in recommendations that can be shared? Have liability premiums historically reflected the level of exposure accurately?

The Insured

Have there been frequent changes in ownership or franchise affiliation? Is the insured established in the industry and/or local community? Does the full schedule of Named Insureds align with your expectations of the size and scope of the risk you are insuring? Is there consistency between historical revenue and payroll over time? Can you gauge the insured’s awareness of human trafficking and their willingness to implement risk mitigating controls?

The Employees

Is turnover a concern? Are background screenings performed? Is an employment service used to fill positions? What wages are paid to various employee positions? How many employees are on‑site during each shift? What is the total number of employees (full time, part time, and full-time equivalent)? Are employees trained in recognizing indicators consistent with human trafficking?

The Franchise (where applicable)

What is the relationship between franchisee and franchise? Are contractual agreements reviewed regularly? What expectations does the franchise have for the individual franchisee’s risk management protocols? Does the franchise provide any specific support, direction, or training for overall operations, including identifying indicators of human trafficking? Can on‑site management implement policy or procedural changes without franchise approval?

The Location

Are security cameras in use in all common areas, including the parking lot? Is there on‑site, 24‑hour security personnel? Is there a single entry point for room access? Are the premises clean and well maintained? When was the last renovation completed and what work was performed? What are the characteristics of the surrounding neighborhood?

The Website and Google Earth

Does the street view of the property and surroundings offer a better perspective than what was presented in the application? Do on‑line reviews reveal consistent themes about a property, and can such reviews provide an underwriter with a better appreciation of cleanliness, clientele, and the surrounding neighborhood? Are rates and reservation requirements consistent with your expectations and risk appetite?

While this list of questions and responses is not exhaustive, it highlights the importance of viewing underwriting considerations holistically. An underwriter’s curiosity and commitment to gathering meaningful information can be the key to distinguishing a risk worth writing from one to decline. Of course, underwriting is just one component of a carrier’s broader strategic approach to addressing human trafficking.

Coverage Forms

While not a failsafe, coverage forms with a policy-level exclusion may help to mitigate exposure. As noted earlier, many carriers have developed their own exclusions. ISO’s human trafficking exclusion release (CG 4049 01 26 & CU 3471 01 26) is not only timely for those carriers who have yet to develop a form but also reflects the industry’s push for coverage clarity.

Loss Control and Claims – Essential Components of Risk Management

- Proactive Approach – Providing insureds and their employees basic training on how to recognize key indicators of human trafficking.

- Reactive Approach – Conducting site evaluations or investigating a claim situation with a focus on identifying indicators of human trafficking.

Broadening the Lens on Human Trafficking

While much of the exposure focus is on sex trafficking at hotels/motels, it is important to recognize that human trafficking encompasses a wider spectrum. The exploitation of adults or minors for forced labor or criminal exploits can affect a variety of industries, not just hospitality.

Hotels and motels are commonly included in commercial insurance portfolios, which explains the heightened industry awareness driven by statistics, media coverage, and legal cases. However, other sectors within these portfolios are also vulnerable to human trafficking risks and underwriters should remain vigilant and consider exposure across all industries, not just those currently in the headlines.

- Forced or Exploited Labor – Agriculture, construction/contracting services, food suppliers/processors, restaurants, industrial/factory operations, beauty and healthcare services, convenience stores, hospitality, domestic services

- Transportation of Human Beings – Trucking, bus, rail, or other transportation hubs

- Housing of Human Beings – Apartments, boarding homes, self-storage facilities, warehouses, camps

As the use of a human trafficking exclusion becomes more commonplace for hotel/motels – in many cases it is a mandatory exclusion for this class on casualty lines – carriers should also consider its implementation for other classes as well.

Addressing Human Trafficking as an Emerging Casualty Exposure

As an emerging casualty exposure, the time for insurance carriers to act is now. While sound underwriting, risk management and claims handling are important components of mitigating human trafficking risk, they may not be sufficient on their own.

Given the potential breadth of exposure and the increasing number of recent court cases, these approaches have the potential to fall short of coverage intent. As part of a comprehensive strategy, we recommend adding a human trafficking exclusion – where appropriate and in consultation with coverage counsel – to help clarify coverage and manage emerging liability.

At Gen Re, we’re watching developments in risk exposures related to human trafficking. We’re also monitoring the actions that individual insurers are taking, and how the courts are responding. To learn more about this complex issue or to discuss the sample exclusion our team has developed, don’t hesitate to reach out to us or your Gen Re representative.

- Michaela Towfighi, Julia Jacobs, “Sean Combs Faces Not Just a Sentencing, but a Host of Civil Cases”, The New York Times, July 4, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/07/04/arts/music/sean-combs-diddy-civil-lawsuits.html.

- Ibid.

- Hurubie Meko, “Judge Will Not Unseal Grand Jury Papers of Maxwell, Epstein’s Companion”, The New York Times, Aug. 11, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/08/11/nyregion/jeffrey-epstein-ghislaine-maxwell-transcripts.html.

- Understanding Human Trafficking – Fact Sheet, U.S. Department of State, Jan. 20, 2025, https://www.state.gov/what-is-trafficking-in-persons.

- About Human Trafficking, U.S. Department of State, https://2021-2025.state.gov/humantrafficking-about-human-trafficking/#:~:text=Trafficking%20Are%20There?-,Human%20Trafficking%20in%20the%20United%20States,child%20care%2C%20and%20domestic%20work.

- Ibid.

- U.S. Customs and Border Protection, https://www.cbp.gov/border-security/human-trafficking.

- Human Trafficking Legal Center, “Using Civil Litigation to Combat Human Trafficking, 2003-2023” https://htlegalcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/Civil-Litigation-Report-2023.pdf.

- International Labour Organization, “ILO says forced labour generates annual profits of US$150 billion,” https://www.ilo.org/resource/news/ilo-says-forced-labour-generates-annual-profits-us-150-billion.

- Id. at note 8.

- Human Trafficking Key Legislation, U.S. Department of Justice, Aug. 23, 2023, https://www.justice.gov/humantrafficking/key-legislation.

- Ibid.

- David J. Buishas, “Human trafficking statue presents growing risk for the hospitality industry and its insurers”, Zywave Professional via Bates Carey, June 26, 2024, https://www.batescarey.com/files/BatesCarey%20Human%20Trafficking%20Article_Advisen.pdf.

- Valentina Pasquali, “Key Issues Emerge Around Hotels’ Liability for Sex-Trafficking,” Real Estate Authority, Nov. 18, 2022, https://www.law360.com/real-estate-authority/articles/1550510/key-issues-emerge-around-hotels-liability-for-sex-trafficking-.

- Id. at note 13..

- National Statistics, National Human Trafficking Hotline, https://humantraffickinghotline.org/en/statistics.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Valentina Pasquali, “Hotels’ Push To Counter Sex Trafficking Wins Mixed Reviews”, Law360, Nov. 18, 2022, https://www.law360.com/articles/1551204/hotels-push-to-counter-sex-trafficking-wins-mixed-reviews.

- Aleeza Furman, “Days Inn Agrees to Pay $24M to Settle Sex Trafficking Claims”, The Legal Intelligencer, Feb. 2, 2023, https://d11upr8lrcn9x7.cloudfront.net/www.klinespecter.com/s3fs-public/2023-02/trafficking-legalintel020223.pdf.

- Faith Williams, “Kline & Specter Wins $37.5M For Sex-Trafficking Victims”, Law360, https://www.law360.com/articles/1730783/kline-specter-wins-37-5m-for-sex-trafficking-victims.

- Chart Riggall, “Ga. Motel Settles Sex Trafficking Suit Days Before Trial”, Law360, July 21, 2025, https://www.law360.com/articles/2367070/ga-motel-settles-sex-trafficking-suit-days-before-trial.

- Ibid.

- Chart Riggall, “Sex Trafficking Survivor Wins $40M Verdict From Ga. Motel”, Law360, July 15, 2025, https://www.law360.com/articles/2365214/sex-trafficking-survivor-wins-40m-verdict-from-ga-motel.

- Chris Larson, “Travelers Unit Involved in Record $40M Verdict for Underage Trafficking at Motel”, p&c specialist, July 23, 2025, https://commercial.pandcspecialist.com/c/4926334/676784?referrer_module=searchSubFromPCSC&highlight=northbrook.

- “Insurer Must Defend Ga. Hotel In Sex Trafficking Suit”, Law360, Sept. 17, 2024, https://www.law360.com/insurance-authority/articles/1879698/insurer-must-defend-ga-hotel-in-sex-trafficking-suit; Northfield Ins. Co. v. Northbrook Indus., Inc., 749 F. Supp. 3d 1325 (N.D. Ga. 2024).