-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Expertise

Publication

Florida Property Tort Reforms – Evolving Conditions

Publication

Is Human Trafficking the Next Big Liability Exposure for Insurers?

Publication

When Likes Turn to Lawsuits – Social Media Addiction and the Insurance Fallout

Publication

Generative Artificial Intelligence and Its Implications for Weather and Climate Risk Management in Insurance

Publication

Engineered Stone – A Real Emergence of Silicosis

Publication

Who’s Really Behind That Lawsuit? – Claims Handling Challenges From Third-Party Litigation Funding -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Publication

Understanding Physician Contracts When Underwriting Disability Insurance

Publication

Voice Analytics – Insurance Industry Applications [Webinar]

Publication

GLP-1 Receptor Agonists – From Evolution to Revolution U.S. Industry Events

U.S. Industry Events

Publication

Always On: Understanding New Age Addictions and Their Implications for Disability Insurance

Publication

Dying Gracefully – Legal, Ethical, and Insurance Perspectives on Medical Assistance in Dying -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

Compound Perils - Is Wildfire Season Having an Impact on New COVID-19 Cases in the U.S.?

September 29, 2020

Sara Goldberg

Region: North America

English

This has been the worst wildfire season in history for many parts of the West Coast of the U.S. and, with several large uncontained complexes still raging, the season is still underway. At the same time, the growing number of COVID-19 cases appears to have subsided just as the wildfires began to spread, nonetheless nearly 230,000 new cases were recorded in the month of August in the West Coast states alone.

We are witnessing two extreme events in parallel: largely uncontrolled wildfires and a largely uncontrolled pandemic. Independently, both these events are devastating for the communities affected and present significantly more pressing issues than investigating any causality between them. Nevertheless, they are an excellent example of the increasing need to investigate compound or composite perils and factor them into our stress testing and industry discussions.

It is worth noting two other recent examples of potential composite perils. New South Wales, Australia, had its worst bushfire season on record this past January, with acres burned on a scale that makes the average wildfire complex in California look small, but that was, thankfully, shortly before COVID-19 took hold in Australia. While not a natural disaster, the catastrophic explosions that rocked Beirut in August provide another clear example of one large-scale event colliding with another, as the blasts led to a tripling of COVID-19 cases.1

The industry has flagged solvency scenarios with multiple extreme events in the past, but mainly as a theoretical exercise. Given the events of 2020, such scenarios no longer seem far-fetched. Recent announcements such as those by New Zealand’s Reserve Bank and the Department of Finance in New York highlight the potential impact of climate change on the financial services sector.2,3 Indeed, climate risk is now included as part of Own Risk and Solvency Assessment (ORSA) reporting expectations.4

Positive Feedback Loops

A positive feedback loop - where one risk feeds another - can look very simple. For example, the mass installation of air conditioning in Europe to counter an increase in heat waves may actually exacerbate global warming; likewise, the methane from permafrost melting only serves to increase the rate at which it melts. The notion of compound perils is not a new one. The synergetic impact between climate change and migration has been extensively studied in politically at-risk areas, such as Lake Chad and Sudan. It’s acknowledged that connected extreme events may indeed pose a systemic risk in the future for the insurance industry.5

Today in the industry we need not look to Sudan; compound perils have emerged in our policyholders’ backyards. Returning to the subject of wildfires in the U.S., the last thing on an evacuated (or burned-out) family’s mind is to check the L.A. Times or Johns Hopkins maps to determine where the active COVID-19 case density is lowest, much less whether they could be exporting cases themselves. Understandably, they look to the weather forecast and which way the wind is blowing to work out their next steps, but their choices could, in turn, expose them to COVID-19 or contribute to its spread.

So, is a feedback loop actually occurring here? Anecdotally, the pieces are there in theory:

- Due to COVID-19, social gatherings are being pushed outside. At least one significant fire is known to have been caused by a gender reveal party in the woods (though most are caused by lightning).6

- Over 7,000 properties have been lost so far, with many more power outages and evacuations adding to (at least temporarily) homelessness in Oregon.7 Will this trigger the further spread of COVID-19?

- Polluted areas have been shown to fare worse in COVID-19 prognoses,8 and in several areas of California the air quality index (AQI) has been treacherous for sustained periods.9

- Testing is widely accepted as an important for keeping the pandemic at bay, but air quality was noted as hampering testing in eastern Washington.10

- Lastly, deaths and injuries related to wildfires and other natural catastrophes - such as hurricanes - may be exacerbated this year, as a result of people opting to avoid public storm shelters and hotels.

What Does the Data Show?

What can analysis of data for wildfires and COVID-19 cases tell us about whether synergy between the two events truly exists? Unfortunately, it’s complicated to explain in a short article. Proving causality is nearly impossible, and even the correlations are not clean cut here as there is a lot of noise around the signals.

A couple of data points indicate that counties adjacent to Tehama County (the heart of one of the main California fire complexes in August) are exhibiting a COVID-19 case trend worse than in non-neighboring counties (e.g., in adjacent Butte County). But it is difficult to provide conclusive evidence for or against the theory. The numbers for new COVID-19 cases are generally improving in the state and it will be difficult to spot whether the wildfires hamper this trend. The trend could just as easily be disrupted by college re-openings, protests, or another cause unrelated to the wildfires.

Secondly, mobility data exists but the final destination of evacuees is not always determined. Some of the counties with intense fires are large, and migration may occur within the county (where COVID-19 case data is only available at a county level). On the other end of the spectrum, some destinations may not be neighboring counties but further afield.

Traveling hours to a hotel in a presumably safe county may prove futile if fire complexes merge. We could take California or even the West Coast as a whole and compare their case trends to other western states without fires, but too many other factors are at play for this to bear meaning.

Thirdly, as mentioned, it is possible that the last thing on evacuees’ minds is COVID-19, or that they will now face additional obstacles to accessing testing. This means that the identification of new cases may be suppressed. A surer metric would be deaths, but this data is in arrears.

Ultimately, we will need to see COVID-19 case data and wildfire data for the completed months of September and October along with documented migration patterns in order to have a fuller picture of COVID-19 developments throughout the life of the fires. In fact, from an income statement and solvency perspective, we would ideally look at the annual picture.

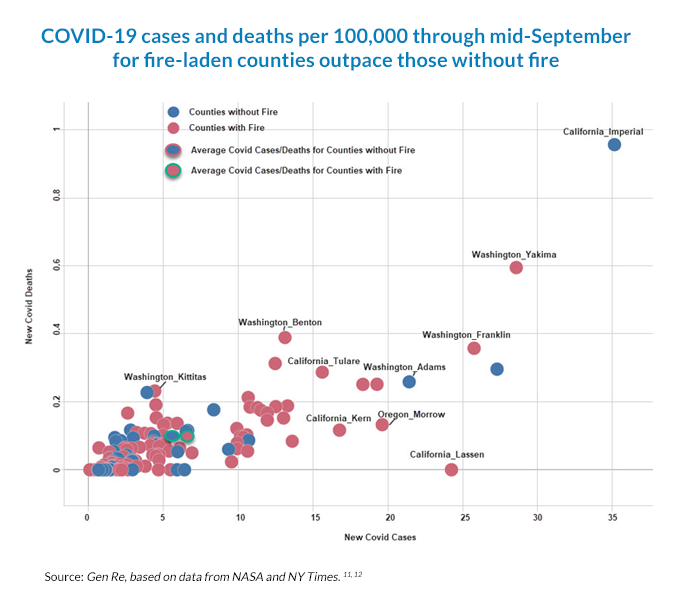

These caveats aside, a relationship between the wildfire-laden counties and strong COVID-19 cases and deaths is broadly present. Out of 132 counties on the West Coast, 95 have logged fires since the beginning of August. Most of these counties carry a heavier COVID-19 burden than the non-fire ones.

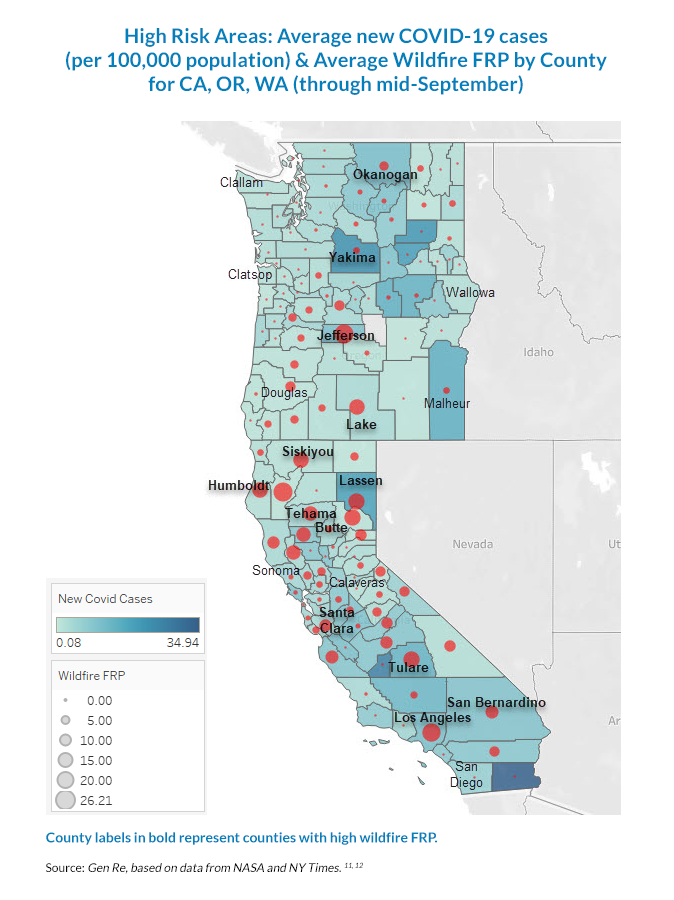

To date the correlation is weak and with noise in the data, and a longer period should be observed for lagging COVID-19 cases and particularly deaths. For the near future, we will be watching the at-risk areas shown in the map below which plots average Fire Radiative Power (FRP - one metric for severity), alongside the incidence of new COVID-19 cases.

What’s the Prognosis?

At this point in time, many laypeople are asking themselves, what else can possibly happen to us in 2020? The average insurance professional is certainly posing the same question. Sadly, the factors behind these particular twin perils - wildfires and the pandemic - will remain in 2021.

Emotionally, we might like to turn to 2021 with COVID-19 well under control - with lessons learned on social distancing, masks, and the right travel restrictions in place - but the continued and deteriorating waves of infections in the United States, western Europe, and Latin America indicate this won’t be the case. We cannot expect the pandemic to disappear from our mortality books until herd immunity is “achieved” or until a combination of at-scale vaccinations and effective treatments are in place - not likely to occur by January 2021.

Similarly, we may hope for a milder wildfire year and fewer extreme weather events in 2021. Yet both the frequency and severity of such events is due in part to climate change which, despite a low CO2 emissions year in 2020, shows no signs of abating.

Forest management practices and property decisions also play a role in wildfire damages, but we will need significant shifts for the underlying risks to be mitigated. With residential properties having crept towards the wildland-urban interface (WUI), and with a one-year ban on cancellation of coverage in the state of California, the same pressures remain regarding rebuilding. The second-to-last thing on a burned-out family’s mind is building code restrictions that apply to their next home. They tend to want the same home - and quickly. Yet this is surely an invitation for history to repeat itself.

With special thanks to my Business Analytics colleagues Nabaneeta Sirkar and Vamsi Krishna Sabbisetty for their collaboration and contributions to this blog.

Endnotes

- https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)31908-5/fulltext

- https://www.bis.org/fsi/publ/insights20.pdf

- https://www.rbnz.govt.nz/financial-stability/financial-stability-report/fsr-november-2018/the-impact-of-climate-change-on-new-zealands-financial-system

- https://www.dfs.ny.gov/industry_guidance/circular_letters/cl2020_15

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41558-020-0790-4

- https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/07/us/gender-reveal-party-wildfire.html

- https://gacc.nifc.gov/sacc/predictive/intelligence/NationalLargeIncidentYTDReport.pdf

- https://www.iza.org/publications/dp/13418/pandemic-meets-pollution-poor-air-quality-increases-deaths-by-covid-19

- https://www.airnow.gov/state/?name=california

- https://www.khq.com/coronavirus/whitman-county-sees-only-11-new-covid-19-cases-as-air-quality-concerns-hamper-testing/article_6d3a0432-f77f-11ea-b16b-bf29d8744596.html

- https://firms.modaps.eosdis.nasa.gov/download/

- https://raw.githubusercontent.com/nytimes/covid-19-data/master/us-counties.csv