-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Expertise

Publication

Structured Settlements – What They Are and Why They Matter

Publication

PFAS Awareness and Concern Continues to Grow. Will the Litigation it Generates Do Likewise?

Publication

“Weather” or Not to Use a Forensic Meteorologist in the Claims Process – It’s Not as Expensive as You Think

Publication

Phthalates – Why Now and Should We Be Worried?

Publication

The Hidden Costs of Convenience – The Impact of Food Delivery Apps on Auto Accidents

Publication

That’s a Robotaxi in Your Rear-View Mirror – What Does This Mean for Insurers? -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Publication

Key Takeaways From Our U.S. Claims Fraud Survey

Publication

Favorite Findings – Behavioral Economics and Insurance

Publication

Individual Life Accelerated Underwriting – Highlights of 2024 U.S. Survey

Publication

Can a Low-Price Strategy be Successful in Today’s Competitive Medicare Supplement Market? U.S. Industry Events

U.S. Industry Events

Publication

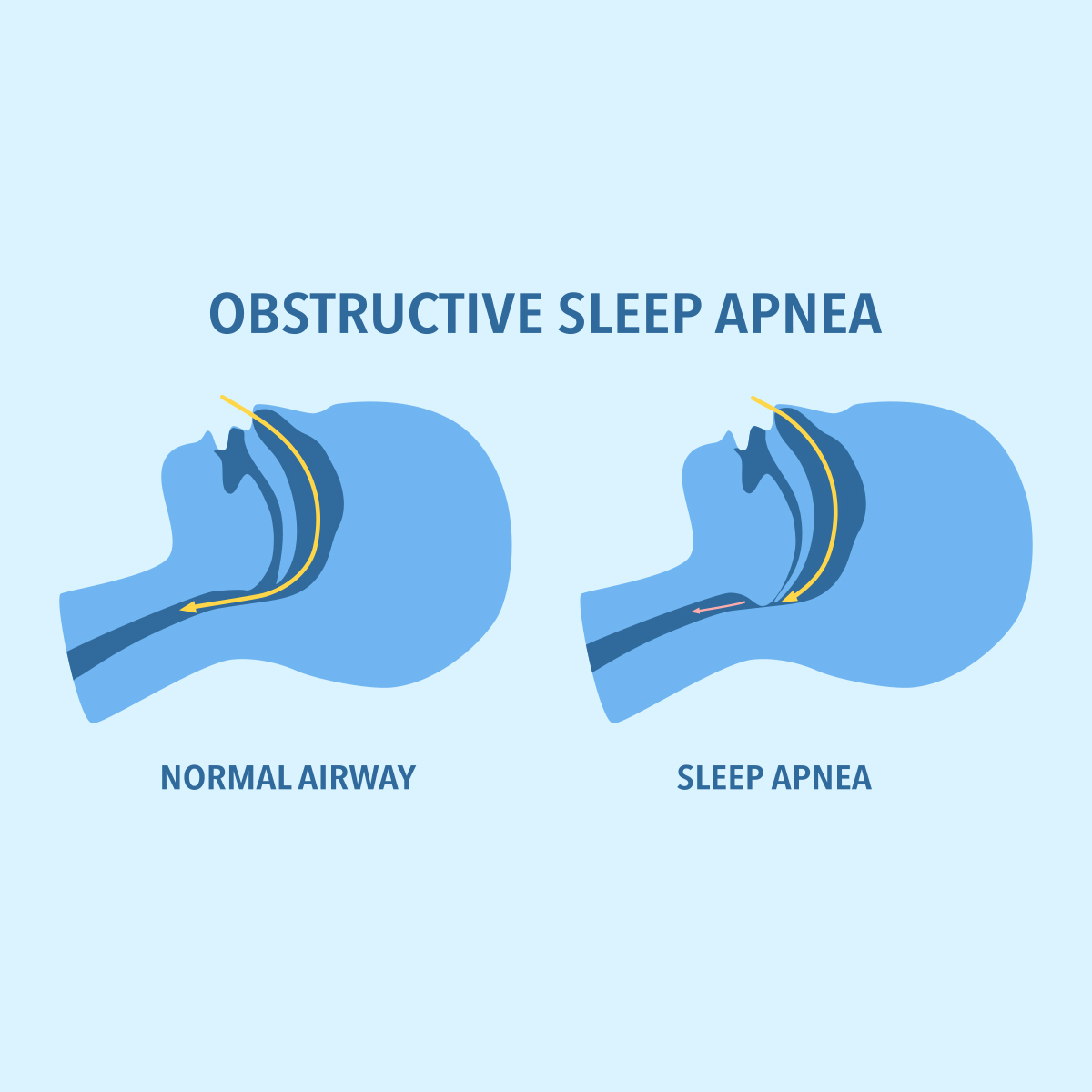

The Latest in Obstructive Sleep Apnea -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

World Cancer Day - Celebrating a Decline in U.S. Cancer Mortality

February 04, 2020

Jean-Marc Fix

Region: North America

English

When the Cancer Statistics, 2020 report was released a few weeks ago, the press rightfully basked in the great news: In the U.S. there were 2.9 million fewer cancer deaths than there would have been if the historically increasing cancer rates had remained level instead of decreasing since 1991.1 The report also said that the U.S. saw the largest single-year drop in cancer death rates ever - a 2.2% drop. Let’s reflect on the causes of this decline, and the likelihood of it continuing in the future.

Cancers With Greatest Impact on Mortality Rates

Cancer is the second most common cause of death overall in the U.S., close behind heart disease, and is the first or second for most age and gender groups.2 It is therefore critical to our understanding overall mortality. Drops in cancer deaths rates have been led by drops in the four of the largest killers: lung, colorectal (CRC), breast, and prostate cancers. Deaths rates for these four are about half of what they were at their peaks (except for female breast cancer which reduced only by about a quarter).3

Lung cancer is still the primary killer-cancer responsible for about one out of five deaths for both men and women. This highlights the importance of controlling the smoking epidemic, and victories on this front have led to the significant - and so far recently accelerating - drops we have enjoyed since the early 1990s for men and the early 2000s for women. There is still much room for progress especially for women but prevalence of smoking can only drop so far. In addition, we see worrying signs with the inroads of vaping and non-traditional smoking at the younger ages.4

As for the other top cancers, we see a slowdown of improvement rates for both CRC and breast cancer, and a significant reduction of the improvement rate for prostate cancer - all since the early 2010s. Melanoma death rates have improved very significantly since 2013/2014, most likely due to the introduction of new therapies. On the other hand, several cancers associated with the human papillomavirus (HPV) infection have increased. What will an increasing use of the HPV vaccination mean for this group of cancers?

Strategies to Improve Impact of Therapies

So, what will the future bring us? In the short term, an ongoing decrease in smoking will continue to drive down deaths from lung cancer and through that, cancer deaths overall. In the long term, five different strategies will vie for impact:

- Control of risky behaviors at the population level - Less impact of smoking, less sun exposure, beginning recognition by the general public that obesity is a risk factor for cancer

- Treatment or vaccination against infections leading to cancers like hepatitis C and human papillomavirus, not to forget HIV and hepatitis B (see recent Gen Re blog explaining hepatitis)

- Increasing impact of precision medicine, especially through pharmacogenomics

- Better understanding of immunotherapy (e.g., vaccines targeted to a person’s own specific cancer cells), the addition of combination therapies and new technologies to fight multi-drug resistant cancer (e.g., nano-particles)

- Better understanding of epigenetics and the microbiome (e.g., using markers from the microbiome to tag cancer cells to prevent them from dodging the immune system)5

Developing Immune System Therapies

I want to spend a minute highlighting the consequences of our ability to read genetic-like code and increasingly write and manufacture custom proteins. I will grossly oversimplify a very complex subject: To be successful, cancer cells evolve multiple mutations, among which are the abilities to capture “energy” efficiently, spread and evade our immune system. Until recently, our treatment options had been to capitalize on that energy differential between normal and cancer cells that renders them slightly more vulnerable to toxic agents, like radiation or chemotherapy. The price to pay was lots of collateral damage including hair loss, vomiting, weight loss and depression. Recent developments have allowed us to take advantage of the defense system our body has evolved over million of years: our killer immune system.

One technology based on our existing immune system is designing custom vaccines, particular to a specific tumor, that highlights the cancer cells to our immune system. Another technology is creating custom immune cells tailored to recognize the cancer signatures: CAR-T cell treatment where we engineer (the C in chimeric) the recognition “nose” (the AR in antigen receptor) of a T-cell or of our immune system. Those are not without danger: if we pick a signature that is not specific enough to the cancer, the immune system will destroy all other cells that coincidentally have that same signature. There are many challenges but an immune therapy for cancer in some form or a combination of forms will open possible new venues for research and for success.6

The Contributions of Care & Follow-Up Data in Research

We need to keep in mind that not all progress in fighting cancer will come from medical advances. Better access to care and better follow-up through electronic health records - and hopefully better research because of that communication - should bring some positive dividends.7 Challenges will remain numerous, foremost the heterogeneity of the processes classified under the umbrella of “cancer” today. While maximizing the impact of testing - as we have seen with the changes in recommended mammograms and prostate cancer - “watchful waiting” will continue to be a tight rope we walk between increasing awareness and increasing costs.

As we have seen with the impact of key drugs in melanoma treatment, access to care will continue exacerbate socio-economic differences. Finally, we are now recognizing the issues associated with two vulnerable populations: survivors of cancer and the elderly.

Regardless of the challenges remaining, our understanding of the genetic code and human ingenuity have provided for many potential roads forward. One thing for sure is that we have only begun to harvest the rewards of that revolutionary understanding.

Endnotes

- Rebecca L. Siegel, et al., “Cancer Statistics, 2020,” CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2020;70:7-30, 8/20/2020, American Cancer Society, https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.3322/caac.21590.

- Ibid. Table 7, Ten Leading Causes of Death in the United States by Age and Sex, 2017.

- Ibid. at Note 1. Figure 7, Trends in Cancer Mortality Rates by Sex Overall and for Selected Cancers, United States, 1930 to 2017.

- Andrea S. Gentzke, et al., Vital Signs: Tobacco Product Use Among Middle and High School Students — United States, 2011–2018 MWWR, February 15, 2019 / 68(6);157–164, https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/68/wr/mm6806e1.htm.

- S. McDowell, et. al., Cancer research insights from the latest decade, 2010-2020. 12/30/19, https://www.cancer.org/latest-news/cancer-research-insights-from-the-latest-decade-2010-to-2020.html.

- C. Rodríguez Fernández, Four new technologies that will change cancer treatment, Labiotech.eu., 10/15/19, https://www.labiotech.eu/features/cancer-treatments-immuno-oncology.

- Louis J. DeGennaro, Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, Advances in cancer research and treatment in 2020, December 2019, https://www.lls.org/blog/advances-in-cancer-research-and-treatment-in-2020-my-predictions.