-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Expertise

Publication

Florida Property Tort Reforms – Evolving Conditions

Publication

Is Human Trafficking the Next Big Liability Exposure for Insurers?

Publication

When Likes Turn to Lawsuits – Social Media Addiction and the Insurance Fallout

Publication

Generative Artificial Intelligence and Its Implications for Weather and Climate Risk Management in Insurance

Publication

Engineered Stone – A Real Emergence of Silicosis

Publication

Who’s Really Behind That Lawsuit? – Claims Handling Challenges From Third-Party Litigation Funding -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Publication

Understanding Physician Contracts When Underwriting Disability Insurance

Publication

Voice Analytics – Insurance Industry Applications [Webinar]

Publication

GLP-1 Receptor Agonists – From Evolution to Revolution U.S. Industry Events

U.S. Industry Events

Publication

Always On: Understanding New Age Addictions and Their Implications for Disability Insurance

Publication

Dying Gracefully – Legal, Ethical, and Insurance Perspectives on Medical Assistance in Dying -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

Workforce Ageing and the Implications for Group Insurance Pricing in Australia

January 25, 2016

Region: Australia

English

It is not common practice in the group insurance market in Australia to price specifically for underlying population trends, especially not for smaller schemes commonly encountered in the corporate segment. However, such smaller trends can have an impact, and this article discusses and quantifies the impact of one of them.

When pricing group insurance arrangements, it is common to offer a unit rate for schemes with more than 50 members, along with a guarantee period attached to it; a three-year period remains common in the Australian market for smaller corporate schemes.

When applying an aggregate unit rate for a scheme with a guarantee period, an inherent business mix risk is included, which increases with the period of the rate guarantee. It is generally assumed that the risk of significant change in the gender, occupation and age mix over the recent past and within the guarantee period is within acceptable tolerance levels. However, membership movement triggers are normally put in place to provide protection against larger movements in membership (normally greater than 25%).

Not generally addressed or protected within group products, is the impact of systemic changes in the workforce. Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) data1 shows that the workforce has been ageing consistently over the past 15 years, if not longer. Graph 1 shows the gradual increase in average age of the employed workforce classed as employees (excluding self-employed and sole traders, who are a more relevant sample for group corporate insurances) from 1999 to 2014. Over this period the average age has increased by 0.18 years each calendar year, a rate that may appear innocuous but with claim rates for group life and salary continuance risks increasing at around 10% for each year of age from about age 40, the impact can be significant.

Consider a simple case where a group risk is being priced with a unit rate guaranteed for the next three years, based on the prior five years’ claim experience, and full credibility is applied to the experience. Without an expectation of workforce ageing, and all other things being equal, the observed unit rate for the prior five years may be assumed as the appropriate unit rate for the next three years.

Using an ageing assumption consistent with ABS data, the expected average age over the claim experience is 4 x 0.18 years = 0.72 years younger than during the rate guarantee period. With rates assumed to increase at about 10% for each year of age, the appropriate unit rate for a fixed level of cover for the next three years would then be about 7% higher than observed in the previous five years. The implication of this is that working without an assumption of workforce ageing could impose a significant strain on profit margins.4

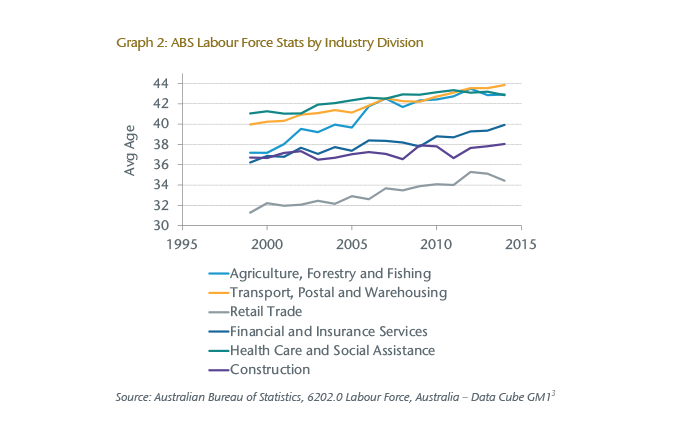

The impact of ageing within different industries was also examined, with some industries experiencing more significant ageing than others, as Graph 2 shows.

Some industries, such as Construction and Healthcare, have shown slower rates of ageing compared to Agriculture, Transportation and Finance/Insurance, for example, but ageing has been present to some degree across all industry groups over the last 15 years.

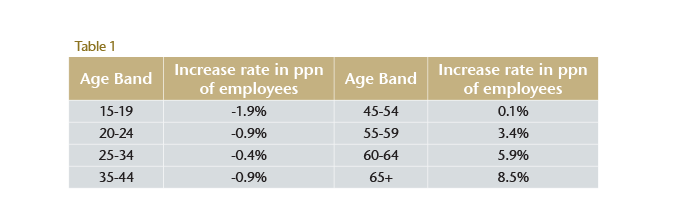

Based on ABS statistics for all industries combined, the average rate of change for the proportion of employees by age group over the last 15 years has been as stated in Table 1.

With government policy including an increase in the normal retirement age, it is not unreasonable to assume that a similar trend will continue in the foreseeable future.

Impacts on Pricing of Common Group Insurance Products

Gen Re has undertaken a detailed assessment of the pricing impact of workforce ageing in various common group product and benefit scenarios. It included the following assumptions:

- General workforce age distribution consistent with ABS data as of January 2014

- Past/future workforce growth rates by age band consistent with the average rate over the last 15 years

- Presence of a promotional salary increase scale of average 1% pa up to age 50

- Benefit-weighted gender mix of 60% male, 40% female

- Claim cost rates as per Gen Re’s standard group corporate pricing basis in Australia

Note that the results are not very sensitive to the promotional salary scale, nor to the gender mix assumed. The implication of the promotional scale is that the average salary level for a 50-year-old will be around 30% higher than that for a 25-year-old. Based on the ABS data, the age distribution and workforce growth rates by age band result in an increase in average age of about 0.2 of a year each year.

Group Life

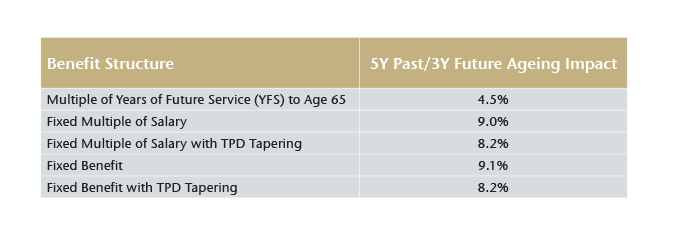

Gen Re has examined the following common structures for group life benefits (Death + TPD):

- Multiple of Salary x Years of Future Service (YFS) to Age 65

- Fixed Multiple of Salary

- Fixed Multiple of Salary with TPD Tapering (5Y to age 65)

- Fixed Benefit

- Fixed Benefit with TPD Tapering (5Y to age 65)

Similar to the situation discussed above, where five-year claim history is applied with full credibility to determine a unit rate for the coming three-year rate guarantee period, the impact of general workforce ageing was as follows:

The approach taken to calculate each of these estimates was:

- Test the impact of one year of future ageing on the unit rate based on the above assumptions

- Extrapolate this increase to the period from middle of the experience to the middle of the rate guarantee

The implication of this result is that an unadjusted unit rate quote based on five years’ prior history with full credibility, and quoted with a three-year rate guarantee, would need to be increased by the percentages in the table above to offset the impact of workforce ageing at the rates assumed.

It is apparent that the impact of ageing is reduced where benefits naturally decrease with age, such as with YFS type benefits. This is due to a reduced weighting in the total claim cost to older ages for such benefits. TPD tapering also has some impact in this respect, although at a reduced level.

Where benefits are based on a unitized age scale that reflects the underlying decrement rates, the impact of ageing is eliminated – and can even be reversed if the unit scale is actually steeper than the underlying decrement rates. The application of age rates reflecting the underlying claim rates in calculating premiums also has the same effect.

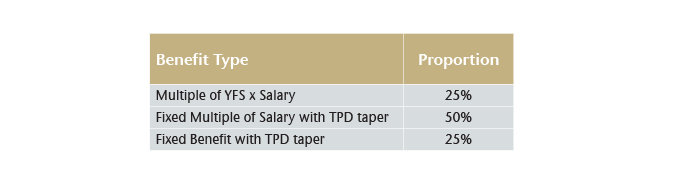

An analysis for Gen Re’s group life exposure in Australia shows the approximate mix of benefits weighted by sums insured in the corporate group life market:

The aggregate 5Y/3Y ageing impact based on this mix is 7.3%. The corresponding impact, where a three-year past history of claims is applied with full credibility to determine a unit rate for a coming three-year rate guarantee period, is 5.4%.

Small schemes will often have age rates applied to protect against volatility in the age mix of the membership, whereas schemes of more than about 50 lives are often unit-rated. The above results suggest that age rates are also appropriate for larger schemes – or that unit rating, if applied, should make allowance for workforce ageing.

Group Salary Continuance (GSC)

Using the same assumptions and approach as for group life above – where a five- or three-year claim history is applied with full credibility to determine a unit rate for the coming three-year rate guarantee period – we have the following resulting impact of general workforce ageing for GSC:

The impact of workforce ageing for unit-rated GSC is higher for 2Y benefit periods than A65 benefit periods because the claim cost rates at older ages continue to increase for 2Y benefit periods. The rates eventually decrease at higher ages for the A65 benefit period as the effective benefit period falls.

Pricing considerations

Workforce ageing is particularly significant in Group Life schemes where benefits are fixed amounts or are fixed multiples of salary, and is significant to a lesser extent for GSC and Group Life where benefits naturally taper to expiry age.

In practice the exposure data available for pricing smaller group schemes is often limited to detailed recent membership data at a specific date and a summarized annual history, normally three to five years, of membership that generally includes only member count and total sums insured. This data does not allow ageing specific to each scheme to be determined. Given the presence of general workforce ageing, one would need to be able to justify why ageing should not be assumed if unit rating is being applied. Historical ageing should be applied to rescale past experience so that experience rating is sound.

It would be desirable to include a quotation data requirement that detailed member data files be provided at each renewal date in the experience period, or at least provided at the start of the experience period, so that ageing can be quantified. Rescaled past experience – where the observed unit rate is adjusted to allow for actual or estimated ageing – would then be appropriate to use in credibility weighting with the expected unit rate based on the recent membership data.

This is not the final step, as general workforce ageing (or ageing based on specific scheme data) should then be applied for future periods to adjust the credibility weighted unit rate to be appropriate at the mid-point of the rate guarantee.

The scenario above does not consider the possible impact of rates of improvement in mortality or morbidity, but this can easily be worked into the rescaling of past experience if required. Future improvement in mortality or morbidity is sometimes assumed in group insurance pricing for unit-rated schemes, although expected worsening from underlying ageing will possibly offset or reverse this.

For larger schemes it is more common to get detailed past membership data that enables adjusting for ageing, specifically in assessing the historical experience, but the possible impact of future ageing then also needs to be considered if a unit rate with a guarantee period is being quoted.

Conclusion

Workforce ageing is a verifiable reality that has a material impact on the pricing of group insurance risks on a unit-rated basis. The impact is highest where benefit rates and/or sums insured do not naturally taper to the maximum cover age. The impact is tempered by manual tapering (e.g. TPD tapering near expiry age), by implicit tapering (e.g. GSC with retirement age benefit periods or YFS benefits for group life) or through credibility weighting, where unscaled experience is used.

The impact of workforce ageing is appropriately eliminated by application of age-based premium ratings, or unitized scales of cover, that reflect the underlying claim rates.

Given the presence of workforce ageing, it is advisable to establish the degree of ageing for a scheme and allow for its consequent impact when quoting on a unit-rated basis. If insufficient data is available to establish whether ageing is present, then the implications of general workforce ageing should be assumed, or its absence should be qualified. The workforce ageing assumption could be industry-specific, given that ABS data is available at industry division and sub-division levels.

If companies have sufficient data available, appropriate assumptions for workforce ageing could be determined from their own portfolios, although credibility of the results would need to be considered.

Endnotes

- http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/6202.0Jul%202014?OpenDocument#Data.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- For an additional perspective on the impact of ageing and interest rates on long-term disability, see “Hitting the Mark “ an article by Jena Breece of Gen Re in the December 2013 issue of Best’s Review.