-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Expertise

Publication

Production of Lithium-Ion Batteries

Publication

Time to Limit the Risk of Cyber War in Property (Re)insurance

Publication

Generative Artificial Intelligence in Insurance – Three Lessons for Transformation from Past Arrivals of General-Purpose Technologies

Publication

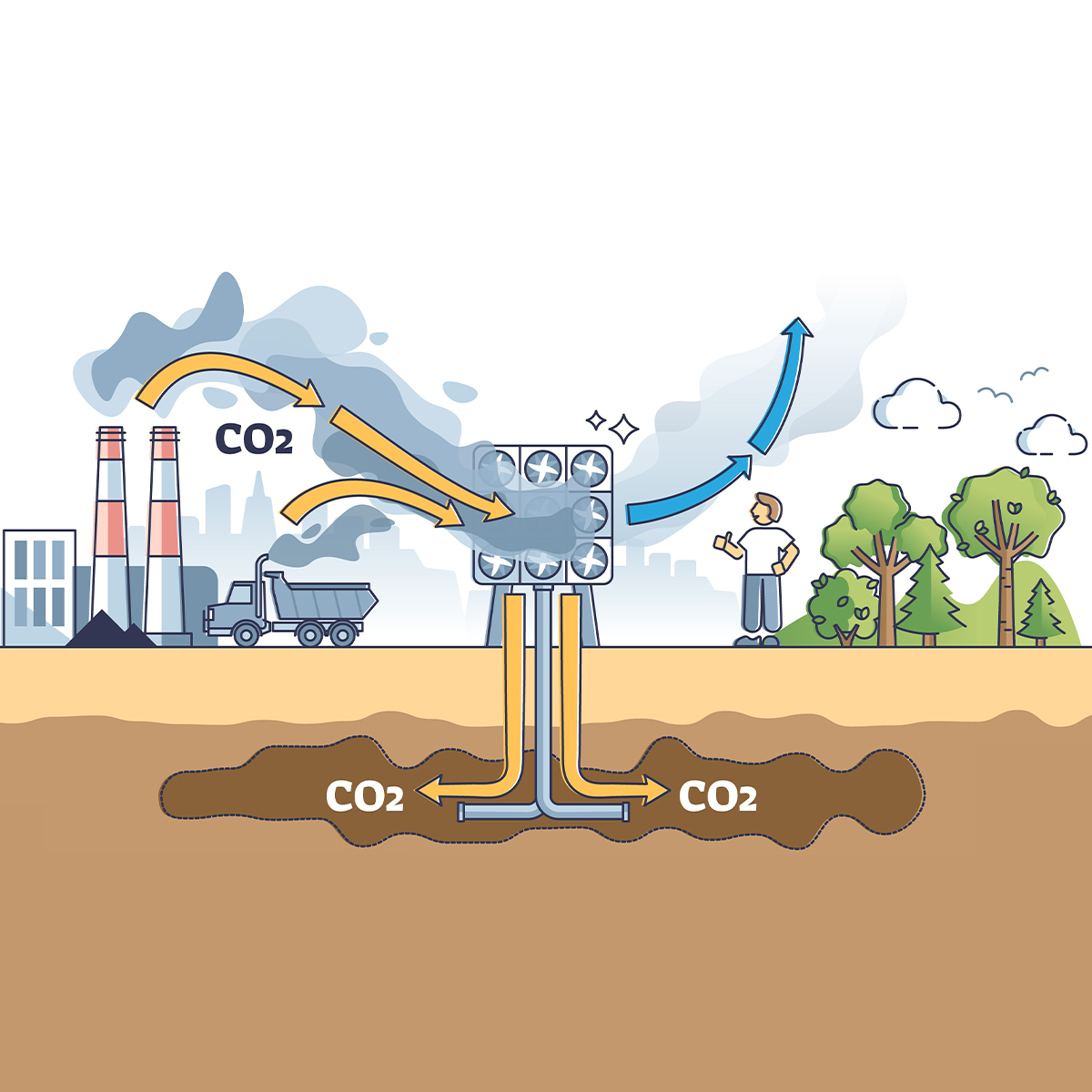

Human Activity Generates Carbon and Warms the Atmosphere. Is Human Ingenuity Part of the Solution?

Publication

Inflation – What’s Next for the Insurance Industry and the Policyholders it Serves? -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

Gen Re’s valuable insights and risk transfer solutions help clients improve their business results. With tailor-made reinsurance programs, clients can achieve their life & health risk management objectives.

UnderwritingTraining & Education

Publication

The Key Elements of Critical Illness Definitions for Mental Health Disorders

Publication

What Are We to Make of Cannabis Use in The Insured Population? Business School

Business School

Publication

Knife or Needle: Will the New Weight Loss Medication Replace Bariatric Surgery?

Publication

Weight Loss Medication of the Future – Will We Soon Live in a Society Without Obesity? Moving The Dial On Mental Health

Moving The Dial On Mental Health -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

Allergies on the Rise: Are they Relevant for Medical Underwriting? [Part 1 of 2]

July 06, 2023

Dr. Sandra Mitic

English

Allergic diseases are the most common chronic non-communicable diseases in Europe today. In the EU, it is estimated that up to 76 million working residents suffer from an allergic disease of the respiratory tract or the skin.1 On top of that, a large European study postulated a lack of treatment or at least inadequate treatment of those affected in up to 90% of patients. This has major socio-economic consequences due to allergy-related absenteeism from work or symptom-related impairment of performance.2

Allergies thus play an important role not only in the national economy, but also in the context of insurance medicine. In recent decades, there has been a steady increase in the number of people with allergies. About 20% of children and over 30% of adults develop at least one allergic disease such as hay fever, allergic asthma and allergic inflammatory skin rashes (neurodermatitis) in the course of their lives.3 And allergies continue to be on the rise. The European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology estimates that in 2025, one in two Europeans could suffer from allergic hypersensitivity.4

What is often dismissed as just banal “hay fever” should be taken quite seriously. Around 40% of people affected develop allergic bronchial asthma in the course of their lives.5 Allergies are also still given far too little attention in the professional environment, e.g. when choosing a profession.

For example: according to the German Allergy and Asthma Association, every year around 25,000 young people in Germany have to quit their job due to allergies. This particularly concerns professions that are associated with an increased risk of allergies, such as bakers, painters and hairdressers.

What is an allergy?

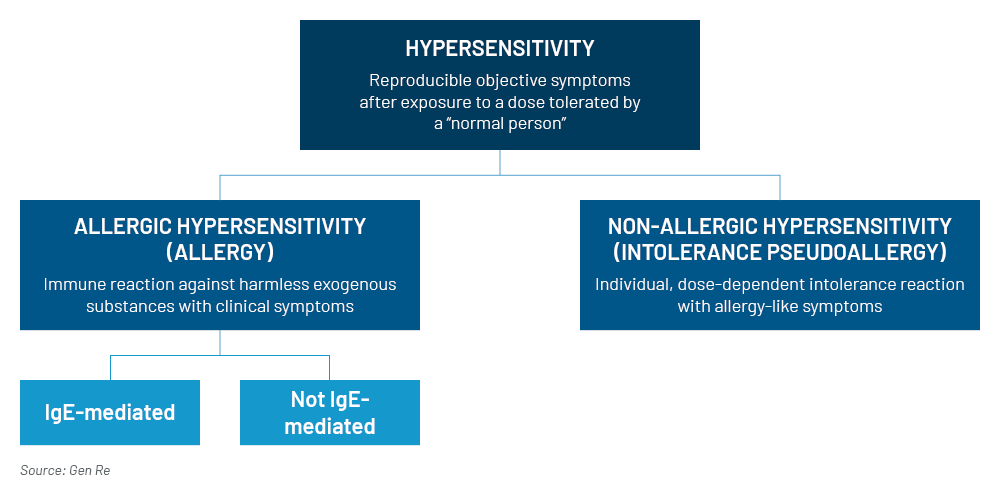

An allergy is a form of hypersensitivity that causes objective symptoms in affected people exposed to a certain, actually harmless substance in a dose that would be tolerated by a “normal” person without any problems. A technical distinction is made between allergic hypersensitivity and the form of non-allergic hypersensitivity (also called intolerance or pseudoallergic reaction) (Figure 1).

The difference is that an allergic hypersensitivity triggers an excessive immune reaction in the human body, which is specifically directed against a substance. It is mistakenly fought by the immune system as a foreign substance in the human organism. Substances that cause this exaggerated reaction of the immune system are called allergens. The immune system produces various antibodies, especially immunoglobulin E (IgE), against allergens. These are then used again and again by the immune system to fight the “foreign” substance when it in contact with the specific allergen again.

The excessive immune reaction is accompanied by a massive release of certain substances that trigger inflammation, such as histamine, serotonin and other vasodilating substances, so the very diverse symptoms of an allergy then occur. The symptoms can vary greatly depending on the organ affected.

Most common symptoms of allergy

Skin: Allergic inflammatory skin rashes (atopic eczema, neurodermatitis)

Pulmonary: Allergic asthma with bronchial obstruction

Nasal: Allergic rhinitis with watery nasal secretion

Eyes: Allergic conjunctivitis with red, itchy and watery eyes

Digestive: Nausea, diarrhoea

The exact reasons for the development of allergies are not fully understood, but there are several factors that are discussed in the field of science, such as excessive hygiene measures, climate change and environmental pollution as triggers of allergies.

Other forms of hypersensitivities that don’t release a specific immune reaction are referred to as non-allergic. There are other pathomechanisms present, such as deficiencies of certain substances in the human organism. For example: lactase is an enzyme for breaking down lactose, a milk sugar. Deficiency of lactase may cause allergy-like symptoms. However, due to the lack of activation of the immune system, it is not defined as an allergic hypersensitivity.

Figure 1 – Definitions of allergy

What is an atopy?

The term “atopy” is defined as a hereditary tendency to react allergically to certain environmental substances and the “overproduction” of IgE antibodies. Atopy is not a disease in itself but describes an activated state of the immune system that increases the risk for an allergic reaction. People with atopy may develop one or more atopic diseases affecting different organs during their lifetime. These diseases typically include allergic rhinitis (hay fever), atopic dermatitis (neurodermatitis or atopic eczema), allergic asthma, and others.

Atopy may be personal or genetically determined. For children with two allergic parents, the likelihood of developing an IgE‑meditaed allergy is 40‑60%.The risk is at least 10% lower if neither parent has an allergy.6

What is the atopic march?

Atopic diseases nowadays effect approximately 20% of the population worldwide.7 The concept of “the atopic march” describes the progression of atopic disorders, usually starting from atopic dermatitis in childhood. Atopy as a personal or familial disposition to IgE‑antibody formation and sensitisation to “harmless” environmental triggers, is considered to be critical in linking atopic dermatitis, IgE‑mediated food allergy, allergic rhinitis and allergic (extrinsic) asthma (Figure 2).8

Affected people may develop a typical sequence of these diseases at certain ages. In some the disease may persist for several years, whereas others may see improvement or even resolution with increasing age.9 The mechanisms of how to “outgrow” an atopic disease are largely unknown but numerous studies have highlighted atopic dermatitis as the first step of the atopic march.

Figure 2 – The atopic march

Although the prevalence of atopic dermatitis in children varies significantly (0.3% to 20.5% among 56 different countries), studies have revealed consistent trends of increasing disease prevalence over time.10 The main risks of progression to rhinitis and asthma in the future are severe and early-onset forms.

What is allergic (extrinsic) bronchial asthma?

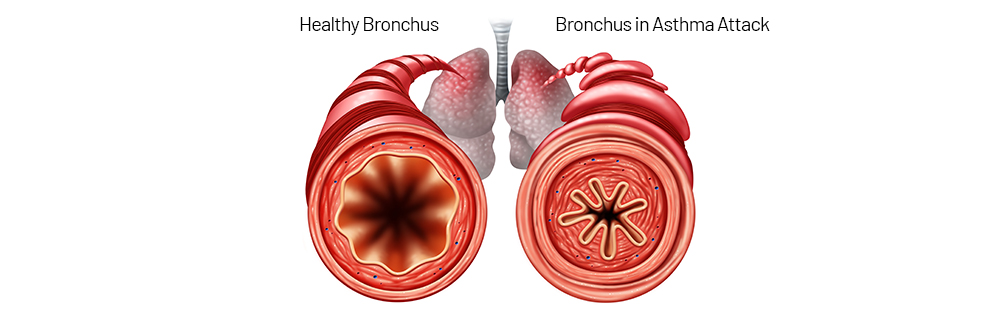

Bronchial asthma is a chronic inflammatory disease of the airways with a variable degree of airway obstruction caused by an inflammatory swelling of the bronchial mucosa (Figure 3). This leads to the typical symptoms of bronchial asthma with a prolonged exhalation phase and the typical wheezing during breathing, which can often be heard from a distance. The obstruction can lead to coughing and acute shortness of breath.

There are various triggering causes for bronchial asthma. In half of the cases it is the allergic form of asthma, also known as extrinsic asthma, which exists due to bronchial hypersensitivity on the basis of an allergic immune reaction. This is triggered by allergens and increased production of IgE, which can also be detected in the blood. This early reaction is often followed by the so‑called allergic late reaction, which causes asthma-typical symptoms.

The allergic form of asthma also includes seasonal asthma, which occurs due to an allergy to certain pollens and occurs according to the respective pollen count. This is often suffered by patients with hay fever whose pollen allergy has undergone a change of stage from the upper to the lower airways. The course is characterised by symptom-free phases with normal lung function and phases with symptoms and below that a deterioration of forced expiratory volume (FEV1) and the FEV1/forced vital capacity (FVC) quotient in lung function.

Figure 3 – Normal (left) and asthma-affected (right) bronchus

What is anaphylactic shock?

An anaphylactic shock is the rare maximum immune reaction to an allergen, which can lead to life-threatening situations. The most common triggers of anaphylaxis include penicillin; acetylsalicylic acid; nuts; egg white; bee or wasp venom; or iodine-containing contrast media used in medical diagnostics.

The anaphylactic reaction usually manifests in varying degrees of severity within seconds to minutes after contact with the allergen. In the lowest degree of severity, there is no acute threat to life and the allergic reaction is mostly limited to the skin with redness and swelling or the formation of wheals.

In more severe cases, the airways may swell up to a severe obstruction due to a contraction of the muscles in the bronchial tubes (bronchospasm). This can lead to acute respiratory insufficiency and an undersupply of oxygen. As a consequence, a circulatory shock may occur and lead to an acute life-threatening situation in which immediate treatment up to and including life-saving measures are required.

The lifetime prevalence of anaphylaxis is currently estimated at 0.05 to 2% in the U.S. and ~3% in Europe. Several population-specific studies have noted a rise in the incidence of anaphylactic reactions, particularly in hospitalisation rates and emergency treatment due to anaphylaxis.11 Fatal outcome is rare and constitutes less than 1% of total mortality risk in atopic people.12

Why is atopy or allergy relevant to insurance medicine?

Anyone who has the predisposition to produce antibodies against a certain substance and already has an allergy has an increased risk of developing allergic hypersensitivity to other substances in the course of life. This can occur as a result of a cross-reaction or as an independent development.

Cross-reactivity in allergic reactions occurs when the proteins in one substance (e.g. pollen) are similar to the proteins found in another substance (e.g. food). It may cause immune system reactions with symptoms to substances that contain similar substances to the already known allergen. For example, people with a birch pollen allergy are often also allergic to apples and hazelnuts.

Another medical risk is the “change of floors” of an allergy. For example, 20 to 40% of people with allergic rhinitis (hay fever) also develop allergic bronchial asthma during their lifetime.

These facts are particularly relevant in the occupational context and already in the choice of a profession. From an insurance point of view, caution is generally required in the risk assessment in the case of an existing allergy. Of course, diseases should always be assessed according to their treatability. With regard to therapy options for allergies, however, it should be noted that the first principle is allergen abstinence. Abstinence to an allergen isn’t always easy to perform, e.g. in the case of contact with allergens in the occupational environment.

Another important principle in the treatment of allergens is the control of symptoms by medication. It should be kept in mind that in the case of long-term treatment with medication, side-effects of medication may have to be expected, e.g. when taking antihistamines, glucocorticoids or immunotherapy.

Furthermore, for immunotherapy, also called hypo- or desensitisation, the actual and lasting effectiveness of the therapy has so far been proved only for a few substances (birch, hazel, grasses, alder, house dust mites, some moulds and bee/wasp venom) in clinical studies. In addition, immunotherapy is more successful with monoallergies than with multiple allergies. It is also more effective in children, adolescents and young adults than in older people.

These are the recommendations for allergy risk assessment:

- Allergies should always be considered in the medical underwriting process.

- There is significant relevance in insurability of occupational disability. For the insurability of life insurance, allergies have a significantly lower relevance, unless allergic asthma is present.

- Due to the possible development of further allergies or the danger of a change of level to asthma, an exclusion of an individual allergy or allergen won’t be sufficiently effective.

- If allergic bronchial asthma is present, the control of symptoms, measured by the frequency of attacks, is decisive.

More than 128 million people in Europe are suffering from allergies resulting in reduced quality of life. One of the top health priorities in the EU is therefore the provision of the best possible treatment and prevention of exacerbation or progression of the disease. In part 2 of this blog series Dr. Sandra Mitic talks about various treatment options and the impact on disability claims.

Endnotes

- Zuberbier T, Lotvall J, Simoens S, Subramanian SV, Church MK. Economic burden of inadequate management of allergic diseases in the European Union: a GA2LEN review. Allergy 2014; 69: 1275–1279.

- Ibid.

- Bieber T, et al. Global Allergy Forum and 3rd Davos Declaration 2015. Allergy 2016; 71(5): 588–592.

- The European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI). Advocacy manifesto. Tackling the allergy crisis in Europe – Concerted policy action needed. June 2015.

- Acevedo-Prado A, et al. Association of rhinitis with asthma prevalence and severity. Nature scientific reports 2022 12:6389. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-10448-w, last accessed, 21 June 2023.

- K. Murphy, C. Weaver. Janeway Immunologie, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-56004-4_14, last accessed, 23 June 2023.

- Bantz SK, Zhu Z, Zheng T. The Atopic March: Progression from Atopic Dermatitis to Allergic Rhinitis and Asthma. J Clin Cell Immunol. 2014 Apr; 5(2):202. doi: 10.4172/2155-9899.1000202. PMID: 25419479; PMCID: PMC4240310.

- D.A. Hill, J.M. Spergel. The Atopic March: Critical Evidence and Clinical Relevance. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018 February; 120(2): 131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2017.10.037.

- Bantz SK, Zhu Z, Zheng T. The Atopic March: Progression from Atopic Dermatitis to Allergic Rhinitis and Asthma. J Clin Cell Immunol. 2014 Apr; 5(2):202. doi: 10.4172/2155-9899.1000202. PMID: 25419479; PMCID: PMC4240310.

- Ibid.

- Yu JE, Lin, RY. The Epidemiology of Anaphylaxis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2018 Jun; 54(3):366–374. doi: 10.1007/s12016-015-8503-x. PMID: 26357949.

- Turner PJ, Jerschow E, Umasunthar T, Lin R, Campbell DE, Boyle RJ. Fatal Anaphylaxis: Mortality Rate and Risk Factors. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017 Sep–Oct; 5(5):1169–1178. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.06.031. PMID: 28888247; PMCID: PMC5589409.