-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Expertise

Publication

Production of Lithium-Ion Batteries

Publication

Time to Limit the Risk of Cyber War in Property (Re)insurance

Publication

Generative Artificial Intelligence in Insurance – Three Lessons for Transformation from Past Arrivals of General-Purpose Technologies

Publication

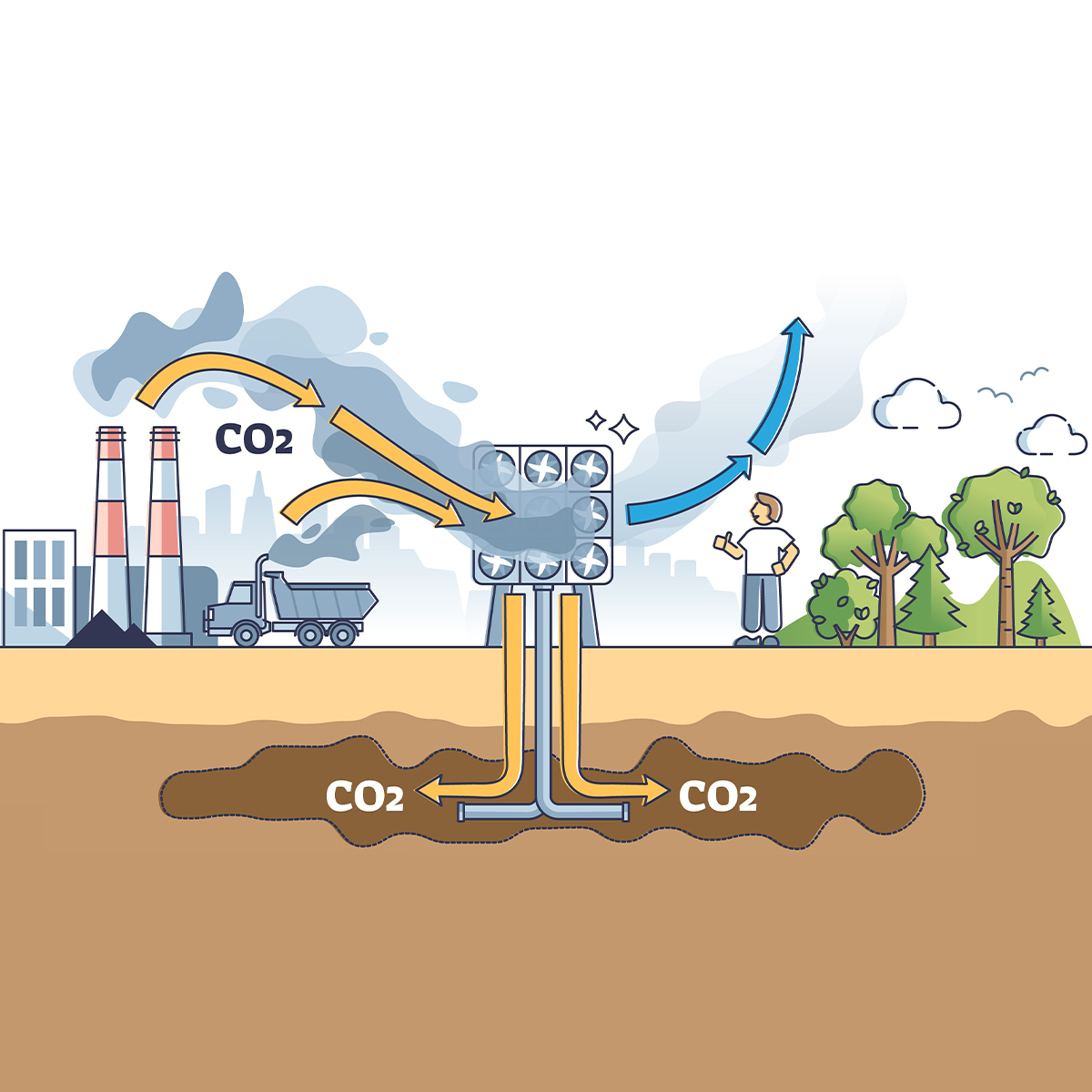

Human Activity Generates Carbon and Warms the Atmosphere. Is Human Ingenuity Part of the Solution?

Publication

Inflation – What’s Next for the Insurance Industry and the Policyholders it Serves? -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

Gen Re’s valuable insights and risk transfer solutions help clients improve their business results. With tailor-made reinsurance programs, clients can achieve their life & health risk management objectives.

UnderwritingTraining & Education

Publication

The Key Elements of Critical Illness Definitions for Mental Health Disorders

Publication

What Are We to Make of Cannabis Use in The Insured Population? Business School

Business School

Publication

Knife or Needle: Will the New Weight Loss Medication Replace Bariatric Surgery?

Publication

Weight Loss Medication of the Future – Will We Soon Live in a Society Without Obesity? Moving The Dial On Mental Health

Moving The Dial On Mental Health -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

The “Gelli Law” - A New Era for Medical Liability in Italy

November 15, 2017

Lorenzo Vismara

Region: Italy

English

On 1 April 2017, Law No. 24/1207, known as the “Gelli Law,” entered into force. One of the main reasons for enacting this law was to address the fact that in Italy many medical professionals took a “defensive” approach when administering medical treatments as they wanted to avoid the risk of becoming the target of criminal and civil liability. The law intends to provide a better structured regulation for the Medical Malpractice insurance market, thereby changing the jurisprudence of the last 15 years.

Main aspects of the law:

The law provides for a “non-contractual” liability of doctors and other medical practitioners employed by hospitals, which means a five-year limitation period with a burden of proof on the claimant’s side. The “contractual” liability, with a 10-year statute of limitation and the burden of proof on the defendant’s side, remains for hospitals and medical professionals in private practice. This means the liability of a medical professional is governed by the relationship with the patient: A direct relationship with a medical professional in private practice is contractual; an “indirect” relationship - when the practitioners are employed by a hospital - is “non-contractual.”

Hospitals, similar entities and individual professionals working on a contractual basis will face the same difficulties as before in defending a case at court. The aggravating element is that in the future, it will likely become more difficult to involve medical professionals who are employed by a hospital or similar entity, as had occasionally been done successfully in the past.

Article 10 of the law determines the obligation for hospitals (and generally for all public and private entities where a medical activity is performed) to have insurance coverage or “any similar measure” that covers third-party liability. The latter aims at authorizing self-insurance. Insurance coverage is also obligatory for professionals practicing in public or private entities but on a private/contractual basis. With regards to “self-insurance,” it is important to note that according to the law, a decree that is still to be enacted will outline how a hospital/entity needs to provide for reasonable reserves that guarantee that any obligations toward third parties can be fulfilled.

This last amendment is important as the majority of hospitals have a certain percentage of their potential liability “covered” by self-insurance, but there is no guarantee for third parties. In the future, hospitals could find it less expensive and more convenient to buy insurance instead of reserving significant assets in their balance sheets in order to cover their potential liability exposures.

Insurance policies that are issued after the enactment of the new law are required to cover incidents that happened during the prior 10 years (article 11). An extended reporting period (10 years) is obligatory in the case of termination of the professional activity. The main provisions of the insurance cover need to be published on the hospital/health care unit’s website.

This part of the law reflects the most recent decisions issued by the Italian Supreme Court (Sezioni Unite Corte di Cassazione) with regard to the “claims made” principle. (Read my 2016 article for more on that.)

Medical professionals/practitioners who are working in hospitals or similar entities (such as public or private healthcare centers), can be found liable - under civil law (art. 2043 Civil Code) - only in the case of a breach of specific guidelines (not yet enacted). If the tort was caused by gross negligence or a voluntary act, the hospital has a right of recourse against the medical professional. The public administration can file a claim with the Italian Administrative Court (Corte dei Conti) and demand compensation with a maximum limit of three times the professional’s annual salary.

The new law determines that insurance covers both “non-contractual liability” (art. 2043 Civil Code) and gross negligence, which now are mandatory for doctors working in hospitals as well: the liability coverage needs to be provided by the employer (i.e., “the hospital”) and the one for gross negligence needs to be bought by the practitioner himself in order to guarantee that a recovery action by the hospital (or by its insurance company) in a case of “gross negligence” can be satisfied.

Considering this law, and a recent internal Gen Re analysis covering various decisions of the Corte di Conti, in our opinion it might become more difficult to obtain a judgment in the instance where a doctor is determined to be liable and must contribute to the compensation of a loss. Consequently, when a hospital has to pay damages, it would be more difficult for it to involve a medical practitioner in the compensation of damages if he or she is employed by the hospital. This is also due to the fact that, according to the new law, the prerequisites to involve practitioners are quite strict.

Last, but not least, article 12 of the law provides for the right of the damaged person to directly sue the insurance company covering the hospital or the professional practicing on a private basis (but not the doctor employed by a hospital or healthcare unit). A similar regulation governs Motor Third Party liability policies in Italy.

Articles 10 and 12 are not yet in force. Decrees that still have to be issued will clarify the extent of their enforceability, especially with regard to the clauses necessary in insurance contracts and clauses that refer to the liability towards third parties.

Before initiating a process, parties need to undergo a faster ADR proceeding previewed by art. 696-bis of the Italian Code of Civil Procedures.

This provision might affect costs for insurance coverages. Although there are numerous policies in the Italian market, covering hospitals that provide for a significant self-retention, the claimant could directly sue the insurance company even in cases where the loss is significantly lower than the attachment point (either because the claimant thinks that his damage is higher or because he doesn’t know how this contractual mechanism works). In such a case, the insurer needs to involve a lawyer (and maybe a forensic expert) who would appear in court to explain how the insurance policy works. Even if the expert succeeds in persuading the court, the insurer has to bear the lawyer’s and procedure costs, although the insurer shouldn’t have been involved at all. Of course, all hospitals and their insurance companies could reach agreements in order to handle this potential issue in a more effective and cheaper way, but it’s important to discuss this topic, considering that the risks involved when not appearing in court are quite high (the company could be fined by the Supervisory Authority for Insurance Companies - IVASS). Furthermore, in some instances where costs were not so high in the beginning, the financial resources of the insurer could be significantly depleted if a large number of such cases occurred.

Since its enactment, this law has triggered significant and numerous discussions for a number of reasons: its relevance for the insurance market; the historically bad results of Medical Malpractice insurance (which led the vast majority of “traditional” Italian insurance companies to leave the market); the significant interest that this line of business has in the European context (including several players from the Lloyd’s Market or countries such as France and the U.S.); the numerous parts of the law that still need to be implemented by the government (enacting specific decrees); and, lastly, the challenging interpretation of the already applicable rules (such as art. 11 in the field of “claims made trigger”).

We are deeply involved in the market discussions: Our recently hosted event, co-organized with MRV Legal, one of the main legal firms practicing in this field, was attended by approximately 200 participants, showing the great interest of and relevance to the market.