-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Expertise

Publication

Use of Artificial Intelligence in Fire Protection and Property Insurance – Opportunities and Challenges

Publication

Public Administrations’ Liability – Jurisprudential Evolution, Insurance Implications, and a Comparative Analysis Across Countries

Publication

Generative Artificial Intelligence and Its Implications for Weather and Climate Risk Management in Insurance

Publication

Engineered Stone – A Real Emergence of Silicosis

Publication

Risk Management Review 2025 -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

Gen Re’s valuable insights and risk transfer solutions help clients improve their business results. With tailor-made reinsurance programs, clients can achieve their life & health risk management objectives.

UnderwritingTraining & Education

Publication

Diabetes and Critical Illness Insurance – Bridging the Protection Gap

Publication

Underwriting the Dead? How Smartphones Will Change Outcomes After Sudden Cardiac Arrest

Publication

Always On: Understanding New Age Addictions and Their Implications for Disability Insurance

Publication

Dying Gracefully – Legal, Ethical, and Insurance Perspectives on Medical Assistance in Dying

Publication

AI Agent Potential – How Orchestration and Contextual Foundations Can Reshape (Re)Insurance Workflows Business School

Business School -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

Reframing the Shape of Long Term Care in Germany

July 13, 2017

Sabrina Link

Region: Germany

English

Long Term Care Insurance (LTCI) is designed to fund basic care needs in later life, such as washing and dressing. Regardless of where individuals receive this support in old age, how it is funded is a growing issue. In many countries, people may augment their compulsory state system with private policies available from insurance companies.

When Germany introduced a compulsory LTCI scheme in 1995, it had three care levels. Later a “level 0” was added to address individuals with limited daily living skills. But from the outset there was criticism of the low emphasis on cognitive aspects as well as the focus on the length of time required for care.

At the start of 2017, the compulsory cover underwent comprehensive reform that reframed the definition of care. This has repercussions for the local private insurance industry and could point the way for future public schemes and private policies elsewhere.

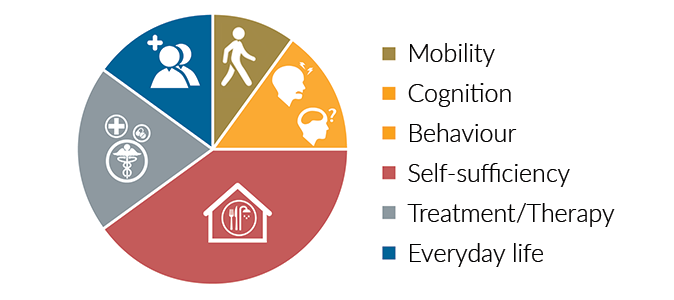

The reform introduced a new "in need of care" definition. It also added a new evaluation instrument for determining the need for care, which comprises six modules:

The allotment of time required for care was replaced by the degree of independence. It is therefore not a question of what the person in need of care can no longer do, but rather what they are still able to do.

The earlier care levels have been replaced by five care grades.

In the past, a person had to actually be dependent on assistance. In the future, it will be irrelevant whether the activity in question actually occurs.

Additionally with regard to inpatient care, the contribution to be paid by the person will no longer be dependent on the care grade; a transition to a higher care grade will therefore not lead to higher contributions.

Additional private LTCI policies are available from both the health and life insurance line - sometimes with considerable differences. However, due to the possibilities to adjust premiums in daily care allowances, the higher guarantee level (including surrender value) in care annuities and varying interest rates, the price-performance ratios of the policies cannot be compared directly.

- For the LTCI policies offered by health insurers, Germany’s PSG II act provides for a special adjustment right for conditions and premiums, and provides even a duty to adjust the tariffs in compulsory private LTCI and nationally subsidised additional LTC insurance policies. Additional private policies follow the procedure in the compulsory private LTC insurance. For one, this means that the new definition of "in need of care" will be used in new business. It also means benefits offered under existing policies have been adapted based on the new definition of "in need of care."

- Products available from the life insurance segment currently use three definitions - the legal definition of "in need of care", a definition based on activities of daily living (ADL), and an independent definition of dementia - as benefit triggers. In future claims assessments involving pre-existing policies, these benefit triggers will have to be taken into consideration if the insured person has not opted to switch to a new policy.

Due to the legal definition, we must ask how a new policy should look. There are currently providers that, for the time being, are sticking with the old care levels or are not using the legal definition at all, favouring the definitions of ADL and dementia instead.

It is worth considering whether to use the new legal definition, which covers both physical and psychological disabilities, exclusively. A separate definition of dementia would then no longer be necessary. On the other hand, a parallel definition of ADL could at least provide partial independence. Both variants are currently to be found on the market.

Care grade 1 serves as a type of preliminary level with an easy-to-achieve minimum score and relatively low mandatory benefits that can only be used for their specified purpose. The calculation of this care grade involves a number of uncertainties as the assumption regarding the number of additional benefit recipients to expect has a major impact. It therefore seems wise to offer no cover or only very low cover for care grade 1, e.g., in the form of a lump sum benefit. Even starting at care grade 1, a waiver of premiums when care is required could become problematic if the premium income is lower than previously calculated. Therefore, for most products on the market, care annuities can only be paid, and premiums only waived, from care grade 2 upwards.

We must also consider whether the assessment of risks in medical underwriting should change. Dementia-related or mental illnesses affecting behaviour and conditions that involve the patient in the monitoring and/or treatment processes are weighted more heavily than in the past. Fundamental changes in the previous assessments are unnecessary. For example, due to the predictability of care dependency it was normally impossible to obtain insurance for psychotic schizophrenia, especially when dementia represented an independent benefit trigger.

The objective of providing more appropriate care grading through the healthcare reform appears to have been achieved. In future, people with cognitive and mental health problems will be shown the same recognition for their limitations as people with purely physical impediments. Some providers have already integrated the new definition of "in need of care" into their products.

It remains to be seen how the private insurance market will develop in light of the reform. Insurers will have to maintain a balance between comprehensive insurance cover and payable premiums, as private LTCI will remain one of the fastest-growing and future-proof products on the German insurance market, not least due to the demographic trend.