-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Trending Topics

Publication

Engineered Stone – A Real Emergence of Silicosis

Publication

Use of Artificial Intelligence in Fire Protection and Property Insurance – Opportunities and Challenges

Publication

Generative Artificial Intelligence and Its Implications for Weather and Climate Risk Management in Insurance

Publication

Public Administrations’ Liability – Jurisprudential Evolution, Insurance Implications, and a Comparative Analysis Across Countries

Publication

Risk Management Review 2025

Publication

Who’s Really Behind That Lawsuit? – Claims Handling Challenges From Third-Party Litigation Funding -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Training & Education

Publication

AI Agent Potential – How Orchestration and Contextual Foundations Can Reshape (Re)Insurance Workflows

Publication

Diabetes and Critical Illness Insurance – Bridging the Protection Gap

Publication

Group Medical EOI Underwriting – Snapshot of U.S. Benchmark Survey

Publication

Why HIV Progress Matters

Publication

Dying Gracefully – Legal, Ethical, and Insurance Perspectives on Medical Assistance in Dying Moving The Dial On Mental Health

Moving The Dial On Mental Health -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

The Reform of Class Action in Italy – How Will it Impact Insurers?

Despite being introduced into the Italian legal system in late 2007, and enacted in July 2009, class actions are still a rarity in Italy. However, with the Italian parliament’s recent introduction of a comprehensive reform framework (known as Law n. 31.) to encourage the use of group representative lawsuits, things could be about to change.

The new law will apply exclusively to unlawful acts that are carried out after the legislation goes into effect in November 2020. One of the biggest changes being introduced refers to the entitlement to act. The reform significantly widens the scope of application of the current rules, providing that whoever holds “individual homogeneous rights” (not only consumers and consumer associations) can bring a class action.

This new version of class action can be brought against all companies, providers of public services, or entities managing services of public utility, concerning acts carried out in the course of their business to seek redress and/or restitution for any type of contractual or tort infringement.

The eligibility filter remains intact in substantially identical terms.1 This has already been criticized by several consumer associations that see it as one of the main obstacles towards the success of class action in Italy.

One of the most discussed and controversial points of the reform relates to how you join the action. The reform widens the time limitation for joining the action and, whereas the current applicable law provides that the last moment for joining the procedure is the decision of admissibility, the new law provides that a member of the class will be able to join the action after the decision on its merit. Therefore, when the new law comes into force, the defendant will probably be unable to assess its potential exposure in terms of the economic compensation to be paid.

Although the new framework is not yet in force, its potential impact on the business sector in terms of uncertainty and risk assessment cannot be ignored. Given the fact that the new law does not modify the eligibility filter, which remains an important hurdle, it is still hard to know whether the reform will result in a significant increase in class actions.

The origins of class action in Italy

Although a legal framework has been in place for several years, it has not been easy to introduce a class action in Italy. Class action law entered the Italian parliamentary debate for the very first time in 2004 to provide effective protection to consumers. The move followed two big cases of financial fraud (Cirio2 and Parmalat3).

Class action was introduced into the Italian legal system by Law n. 244 on 24 December 2007, which added the procedure into the Italian Consumers’ Code, art. 140 bis (which in turn was slightly reformed by law n. 23 in July 2009).

The law provided that only consumers and registered consumer associations were entitled to start a class action. The withdrawal of the requirement of consumer status represents one of the biggest changes introduced by the 2019 reform.

However, as a tool, class action has not gained significant usage. To date, the total number of class actions amount to less than 100. Many of those have been declared inadmissible and only four have been concluded with a decision.

One noteworthy case, started by Codacons (an Italian consumer association), involved the pharmaceutical company Voden Medical.4 A trial phase lasting eight years concluded with a decision awarding compensation of EUR 14.50 in favor of the sole consumer who had joined the class action.

In 2012, Altroconsumo (another well-known consumer association) started a class action against the Italian railway company Trenord. The event occurred on 9 and 10 December 2012, when a power outage occurred that caused moral damage to those affected. Consumers claimed moral damages against Trenord because for almost a week (while it was very cold outside) the train schedule was disrupted, and passengers suffered inconveniences due to train departure delays.

Although the Milan Court of Appeal in 2017 ordered Trenord to pay EUR 100 to each consumer who had joined the action (around 3,000 people), in May 2019 the Supreme Court reversed the former judgement (see ruling n. 14886/2019). The main reason for this decision was the lack of evidence. The Supreme Court confirmed that providing evidence of the damage suffered by each consumer is a minimum requirement to receive compensation for moral damage, which cannot be proven by a generic and unspecified state of anxiety or dissatisfaction.

In summary, the original Italian class action system was not a great success due to the Italian compensation system (tied to a restorative approach as opposed to the U.S. compensation system, in which, in addition to different procedural requirements for class actions, the underlying cause of action may permit punitive damages to be awarded to the class),5 the complexity of the procedure, and the high costs involved.

Notable changes introduced by the reform

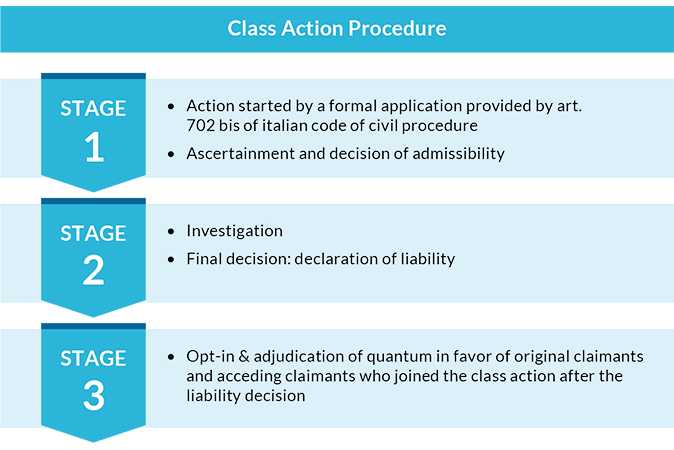

In terms of procedure, the new class action regime is regulated by art. 702 bis of the Italian Civil Procedure Code and consists of three stages. The first stage ascertains the admissibility of the claim; the second investigates the merits and ends with a decision about the liability; the last stage adjudicates on compensation for the original claimants and acceding ones (see graphic).

Now, the instrument of class action is no longer regulated by the Consumer code; the relevant provisions are instead in Heading VIII bis of the Civil Procedure Code and comprise 15 Articles (Articles 840 bis to 840 sexiesdecies).

In addition, a single claimant can now bring a class action because the instrument is no longer restricted to consumer associations.

However, the reform does leave the eligibility filter intact in substantially identical terms. The law provides four cases of inadmissibility of a class action claim:

- Manifest groundlessness;

- Lack of homogeneity of the rights;

- Conflict of interests between the claimants;

- And, the claimant not adequately representing the holders of the relevant homogeneous rights.

The opt-in mechanism, which requires an express will and act to join, remains.

Another change made by the new law consists of the introduction of the class representative (Rappresentante Comune per gli aderenti), appointed by the judge and who is responsible for the allocation of compensation amongst the class members.

To encourage lawyers to use collective action, the reform creates a new model of legal fees: damages-based agreement. In addition to the ordinary fee, in the event of a judgement which confirms the liability, the class representative will receive a further amount proportional to the total number of claimants.

As mentioned, the reform applies exclusively to unlawful acts carried out after the date the reform comes into effect in November 2020.

Potential impact regarding disclosure and insurance

Apart from the procedural changes made by the new law, the expanded discretionary power regarding evidence represents a rather unsettling factor for businesses. The defendant company will be the main holder of the burden of proof. They will have to comply with the disclosure order issued by the judge and provide information and evidence in its possession.

The disclosure order served on the defendant will have a broad area of obligations: article 840-quinquies, VII comma, provides that the judge can order the defendant to disclose evidence or information considered as personal, commercial, financial, or industrial. In addition, the judge is allowed to use statistical data or rebuttable presumptions to establish the defendant’s liability. If the disclosure order is not complied with, a fine of up to EUR 100,000 can be imposed on the defendant.

A related potential problem for organizations facing a class action, in the context of disclosure, is the growing role of social media. This can pose a threat to companies who, to avoid litigation, come under added pressure to settle the lawsuit.

From an insurance perspective, it can be assumed that premium ratings concerning the most affected policies, such as product liability, cyber policies, or D&O, will need to be reviewed. The new law will likely have a direct impact on product liability and cyber risk coverage. For D&O, the potential implications of the reform will be less direct as, following a decision, the defendant could bring recovery proceedings against the directors and officers responsible for the illicit act that gave rise to the class action.

Specific insurance coverage to protect organizations against the costs of class actions does not currently exist in Italy, largely because such litigation is rarely encountered. It remains to be seen whether the reform will result in the market developing customized insurance products: specific coverage for class action litigation expenses related to product liability cases is a possibility.

Initial reactions to the reform

The reform has sparked a lively debate between Italy’s major trade associations. Assonime, the Association of Italian Joint Stock Companies, lodged a strong objection, mainly against the time extension which allows single members to join the action, even after the decision on its merit has been made.

In Assonime’s view, the time extension will represent a serious threat to defendants because they will be prevented from knowing the real “perimeter” of the class and their potential exposure in compensation to be paid until the end of the proceedings.6 Assonime also raised doubts about a general lowering of safeguards to businesses and that the new law could also encourage opportunistic behaviors and complicate case management.

ANIA, the Association of Italian Insurance Companies, did not welcome the reform either, asking for a further extension until January 2021.

Antonio Catricalà, the former president of AGCM, the Italian Competition Authority, was critical of the new law due to the uncertainty it creates and the problem of risk assessment. In his view, insurance availability is also a major issue given that the reform aims to expand access to class action and insurers will have to provide adequate responses.7

As expected, Confindustria, the main association representing manufacturing and service companies in Italy, criticised the reform and asked for a different approach to be taken.

The reform gained approval from the major consumer associations, especially regarding the main scope of enlarging the current usage of class action. However, several consumer associations protested that the eligibility filter remains substantially intact, asserting that the current inadmissibility system works against the new law.

Class actions during COVID-19

When discussing class actions today, it’s impossible to ignore the COVID-19 emergency and its devastating effect on Italy. While it seems unlikely that class actions will succeed in relation to the pandemic, it is worth noting that two have already been proposed.

At the end of April 2020, the Italian consumer association Codacons expressed its willingness to bring an action against the Chinese government due to damages caused by the alleged failures to prevent the spread of COVID-19. They appointed a U.S. law firm to investigate the feasibility of this action.8

Similarly, Rome-based non-profit, ONEurope, launched a multimedia platform to enable consumers to join a class action against the Chinese government, albeit through the U.S. courts.9

The litigation strategy for these potential actions, as well as the potential scope of compensation, remains unclear. Given the highly disparate nature of the rights violated, the eligibility requirement will be a big hurdle for both. In particular, the homogeneity requirement for admissibility will be very difficult to fulfil.

Worth noting, since the reform measures will not enter into force until November 2020, potential class actions related to COVID-19 will likely be subject to the current law. It’s also possible that the disruption created by the pandemic could further delay the introduction of new legislation.

Conclusion

Although the new class action reform has not yet come in to force, its potential impact on the Italian business sector is significant and should be reflected in every organization’s enterprise risk assessment process. However, given that the new law does not modify the eligibility filter, which remains an important hurdle for plaintiffs, it remains to be seen whether the remaining reform measures will truly result in greater use of collective action in Italy.