-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Trending Topics

Publication

Engineered Stone – A Real Emergence of Silicosis

Publication

Use of Artificial Intelligence in Fire Protection and Property Insurance – Opportunities and Challenges

Publication

Generative Artificial Intelligence and Its Implications for Weather and Climate Risk Management in Insurance

Publication

Public Administrations’ Liability – Jurisprudential Evolution, Insurance Implications, and a Comparative Analysis Across Countries

Publication

Risk Management Review 2025

Publication

Who’s Really Behind That Lawsuit? – Claims Handling Challenges From Third-Party Litigation Funding -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Training & Education

Publication

AI Agent Potential – How Orchestration and Contextual Foundations Can Reshape (Re)Insurance Workflows

Publication

Diabetes and Critical Illness Insurance – Bridging the Protection Gap

Publication

Group Medical EOI Underwriting – Snapshot of U.S. Benchmark Survey

Publication

Why HIV Progress Matters

Publication

Dying Gracefully – Legal, Ethical, and Insurance Perspectives on Medical Assistance in Dying Moving The Dial On Mental Health

Moving The Dial On Mental Health -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

Are Centenarians Different – or Just Lucky?

May 10, 2019

Jean-Marc Fix

English

Centenarians are rare, but they are among the fastest growing population segments in the U.S. and throughout the developed world - and what is rare is special. But why are they special? Unfortunately, we humans are better at rationalizing than at rational thought, as the prevalence of superstition throughout history clearly demonstrates.1

As a matter of fact, when researchers looked at evaluation of claims of extreme old age, they encounter a number of archetypes.2 Some of the most interesting and still pervasive myths are: the fountain of youth myth (a special substance will make you live longer); the Shangri-La myth (living in a special place will make you live longer); the village elder myth (where old, generally men, live longer and that’s why our village is the wisest); the spiritual practice myth (special spiritual rituals and practices will make you live longer); and, finally, still quite active today, the national longevity myth (in our country, people live longer because we are superior). Not all myths are necessarily false. There are some areas with a higher density of verified centenarians than others, for example, the famed Blue Zones.

Many in the scientific community believe that there are lessons to be learned, and I agree. As mortality has improved and the number of centenarians has increased, determining the “special element” becomes more difficult as some people are just lucky.

Research has now turned to study supercentenarians who have reached the age of 110 - truly rare in the world with only a few hundred of them identified.3 In fact, documented supercentenarians are a recent phenomenon with one or two emerging in the 1960s and the population exploding, relatively speaking, since the late 1970s.4

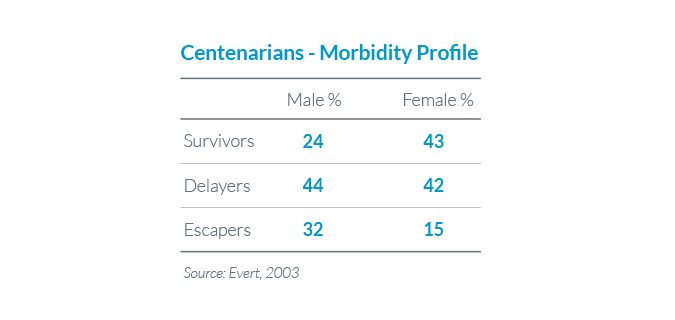

We have known for some time that centenarians fall into three groups:5

- Survivors - People who had an age-associated illness but survived.

- Delayers - People who did not have any disease related to aging until their 80s (the most common group).

- Escapers - People who did not get an age-related illness until past the age of 100. The patterns are quite different by gender, with more women centenarians (three out of four) and supercentenarians (nine out of 10).

Frailty is an important criterion to understanding mortality in the elderly and is commonly reviewed as part of our elderly underwriting. In a recent study by Herr et al., of over 1,000 centenarians in five countries, frailty was defined by weight loss, fatigue, weakness, slow walking speed, and a low level of physical activity. She found that more than 65% of the centenarians had at least three criteria, and over one-third had four or five.6

Paradoxically, research from Kheirbek on male U.S. veterans comparing octogenarians, nonagenarians and over 3,000 centenarians, found that centenarians had less incidence of chronic illnesses than octogenarians. For instance, the rate of hypertension was over 29% in octogenarians but 3% in centenarians.7

A recent article by Gubbi shows that offspring of parents with exceptional longevity, themselves known to live longer, have the same prevalence of obesity, smoking, alcohol use and physical activity as the offspring of parents with usual mortality. On the other hand, they are approximately one-third less likely to have hypertension or cardiovascular disease and two-thirds less likely to have had a stroke.8

Another recent article on the offspring of centenarians by Drury contradicts the numbers for obesity and smoking and adds more dentist visits as a factor because oral hygiene is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease.9 The jury is still out on the risk profile, but what emerges is that centenarians and their offspring are less affected by specific risk factors than the rest of us.

So, is it in the genes?

There is a strong body of evidence for familial longevity that suggests a genetic component. Sebastiani found that centenarians have as many disease-associated gene variants than the general population. What seems to make supercentenarians genetically special may be a higher prevalence of genes countering the effects of the deleterious mutation.10 Genetic analysis of that population shows that there are no magic genes, but a series of genes helping to cope with dangerous risk factors.

This resilience gives rise to the hope that geroscience, which focuses on combatting aging instead of specific diseases, may hold promise for all of us. It is interesting to note that resilience may not just be physical but also mental. A study by Lakomy points to psychological resilience as a predictor of longevity, with an especially significant impact on women, which could explain the gender inequality that we see at the oldest ages.11

We are also learning about the epigenetic (external impact on gene expression), proteomic (how genes are activated and expressed), and microbiome (impact of microbial life in our gut) components of longevity.

Will the drug metformin, typically used in the treatment of diabetes, be the fountain of youth?12 No one knows yet, but I am optimistic that by understanding the complexity of the different layers that contribute to longevity, we are closer to achieving meaningful results in extending life span - and more importantly for society and for us personally, an extension that is healthy.

This blog originally appeared in our e-newsletter series “The Future of Old Age - Insights for Insurers.”

Endnotes

- Centenarians are among the fastest growing population segment: “An Aging Nation: The Older Population in the United States,” Population Estimates and Projections, Jennifer M. Ortman, et al., US Census, May 2014, p25-1140.

- “Typologies of Extreme Longevity Myths,” Robert D. Young, Bertrand Desjardins, Kirsten McLaughlin, Michel Poulain, and Thomas Perls. Hindawi Publishing Corporation, Current Gerontology and Geriatrics Research, Volume 2010, Article ID 423087.

- “Emergence of supercentenarians in low mortality countries,” Jean-Marie Robine (INSERM, Val d'Aurelle, 34298 Montpellier, France) and James W. Vaupel (Max Planck, Institute for Demographic Research, Rostock, Germany).

- Ibid.

- “Morbidity Profiles of Centenarians: Survivors, Delayers, and Escapers,” Jessica Evert, Elizabeth Lawler, Hazel Bogan and Thomas Perls. Journal of Gerontology: Medical Sciences, 2003, Vol. 58A, No. 3, 232-237.

- “Frailty and Associated Factors among Centenarians in the 5-COOP Countries,” Marie Herr, Bernard Jeune, Stefan Fors, Karen Andersen-Ranberg, Joël Ankri, et al. Gerontology, 2018, 64 (6), pp.521-531.

- “Characteristics and Incidence of Chronic Illness in Community-Dwelling Predominantly Male U.S. Veteran Centenarians,” Dept. of Health & Human Services, HHS Public Access, Author manuscript; available in PMC 2018 September 01; Published in final edited form as: J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017 September; 65(9): 2100-2106. doi:10.1111/jgs.14900.

- “Effect of Exceptional Parental Longevity and Lifestyle Factors on Prevalence of Cardiovascular Disease in Offspring,” Dept. of Health & Human Services, HHS Public Access, Author manuscript; available in PMC 2018 December 15; Published in final edited form as: Am J Cardiol. 2017 December 15; 120(12): 2170-2175. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.08.040.

- “Do the Offspring of Centenarians Have Good Health Habits?” J Drury, S Sidlowski, B Leonard, M Hsu, M Mostowy, S Andersen, and T Perls, Innovation in Aging, 2018 Nov; 2(Suppl 1): 31. Published online 2018 Nov 11.

- “The genetics of extreme longevity: lessons from the New England Centenarian study,” Paola Sebastiani and Thomas T. Perls, Frontiers in Genetics, Review Article published: 30 November 2012.

- “Resilience as a Factor of Longevity and Gender Differences in Its Effects,” Martin Lakomý and Marcela Petrová Kafková, Czech Sociological Review, 2017, Vol. 53, No. 3.

- The Targeting Aging with Metformin Trial, American Federation for Aging Research, https://www.afar.org/research/TAME.