-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Trending Topics

Publication

Production of Lithium-Ion Batteries

Publication

Time to Limit the Risk of Cyber War in Property (Re)insurance

Publication

Generative Artificial Intelligence in Insurance – Three Lessons for Transformation from Past Arrivals of General-Purpose Technologies

Publication

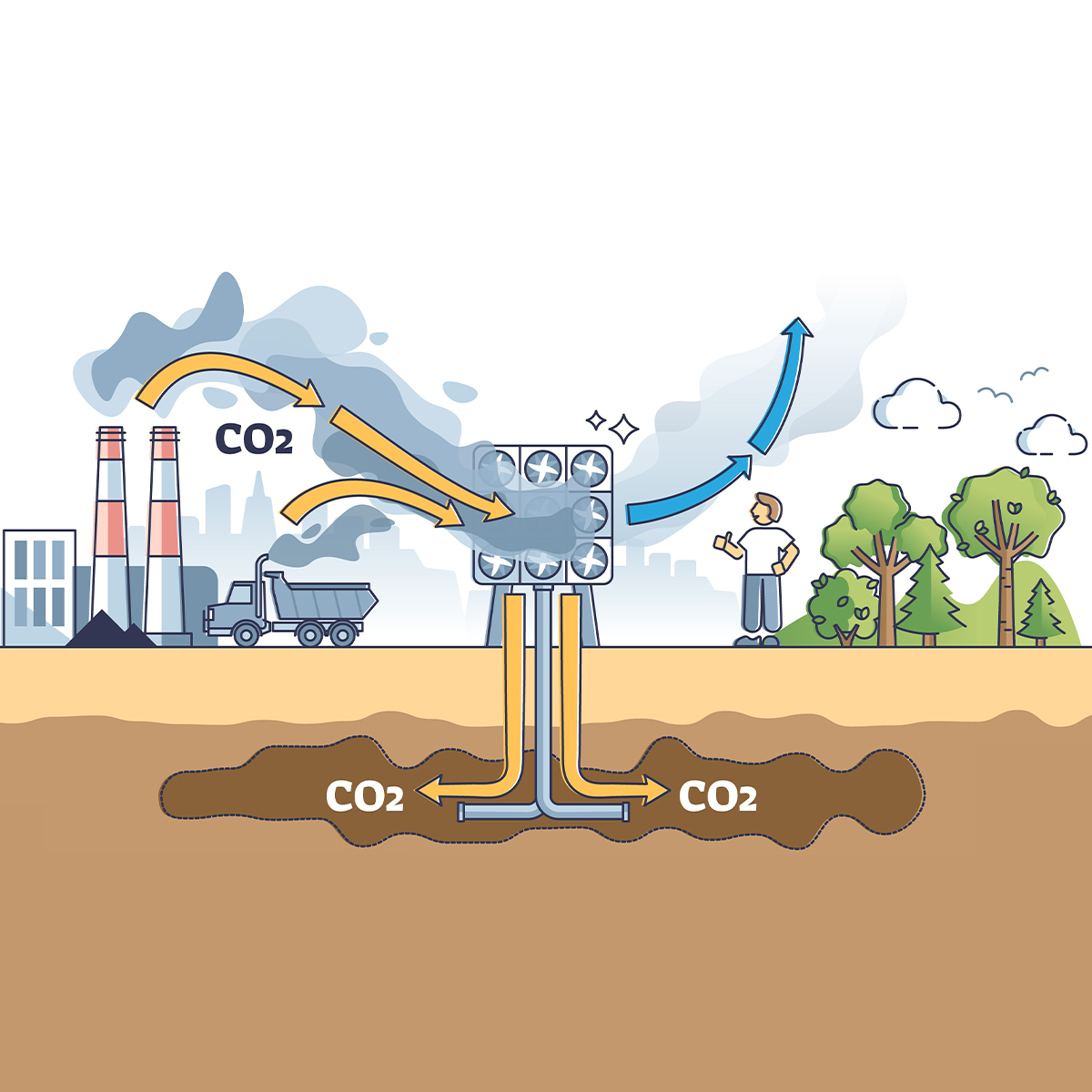

Human Activity Generates Carbon and Warms the Atmosphere. Is Human Ingenuity Part of the Solution?

Publication

Inflation – What’s Next for the Insurance Industry and the Policyholders it Serves?

Publication

Pedestrian Fatalities Are on the Rise. How Do We Fix That? -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Training & Education

Publication

Key Takeaways From Our U.S. Claims Fraud Survey

Publication

The Effects of Heatwaves – A Look at Heat-related Mortality in Europe and South Korea

Publication

The Key Elements of Critical Illness Definitions for Mental Health Disorders

Publication

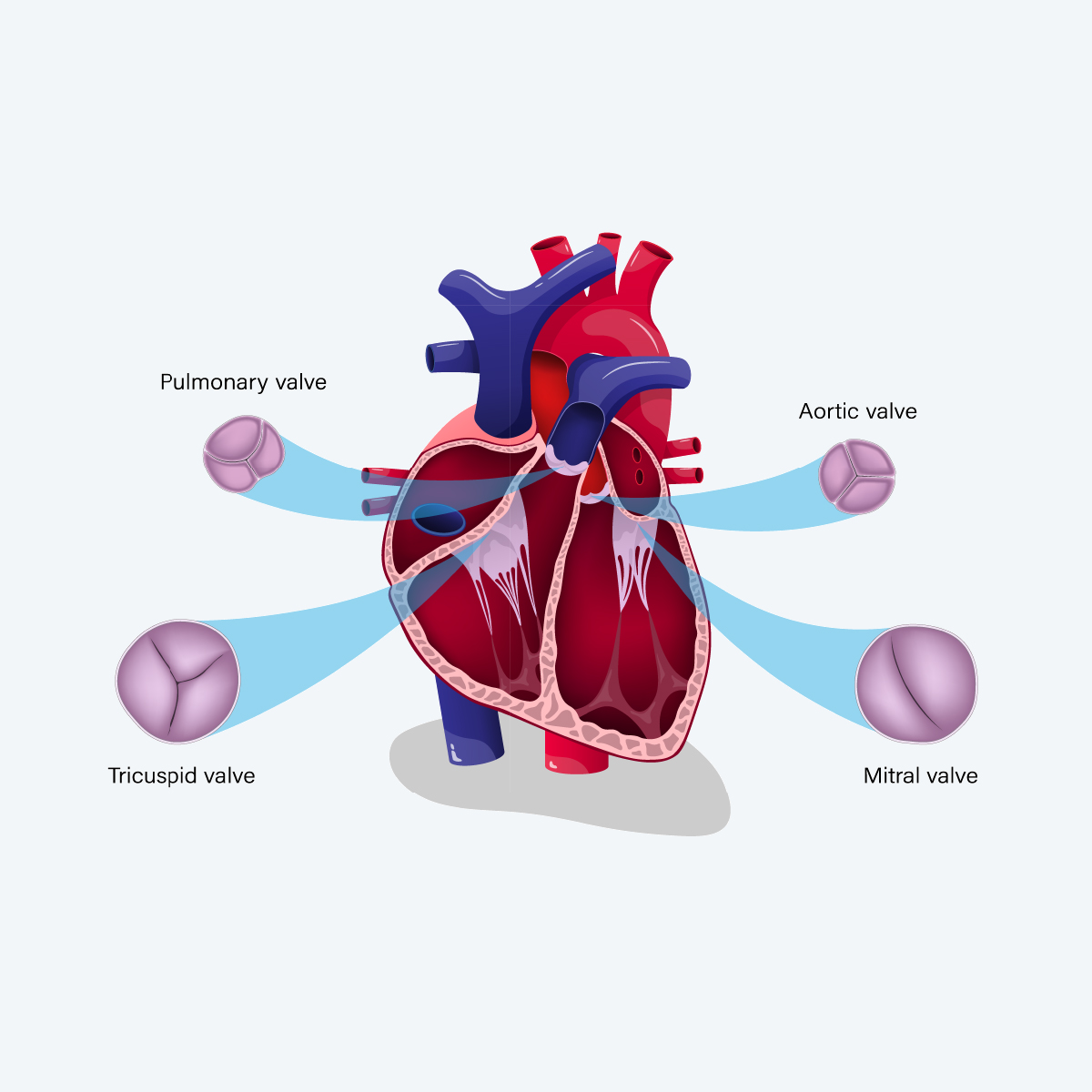

An Overview of Mitral Regurgitation Heart Valve Disorder – and Underwriting Considerations

Publication

Body Mass Index as a Predictor of Cardiovascular Health Moving The Dial On Mental Health

Moving The Dial On Mental Health -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

Are Claims Arising Out Of "Knockoff" Goods "Advertising Injury"?

June 20, 2017

Jim Pinderski and Michael DiSantis, Tressler LLP (guest contributors)

Region: North America

English

How many of us shop at the mall or online and see what we think are name brand items, only to find out upon closer examination that they are well-constructed "knockoffs" at a fraction of the price? What may be attractive to us as consumers can raise a host of issues concerning whether or not coverage may be afforded to the insured producing "knockoffs," particularly as it relates to the advertising of such products.

In some cases, Commercial General Liability insurance policies (CGL policies) will cover certain claims involving "knockoff" goods, but not all claims. CGL policies typically provide coverage for damages because of "advertising injury," and often (although not always) define "advertising injury" to include the use of another's advertising idea or the infringement of certain intellectual property interests in an advertisement. "Advertising injury" coverage does not apply to intellectual property claims unless an advertisement is involved and should only cover damages caused by advertisements, which may include damages resulting from the sale of infringing products.

Careful attention must be paid to policy wording and definitions to determine whether the claim involves an "advertisement" and whether the claim involves infringement of one of the specific types of intellectual property interests covered by the policy. This article addresses a few of the many limitations of coverage and exclusions in CGL policies that may limit or bar coverage for intellectual property claims.

What's an Advertisement?

As its name would suggest, "advertising injury" coverage is limited to claims involving advertisements. But what constitutes an "advertisement" can be a thornier issue than one might assume. The ISO CGL policies since 1998 - revised in 2001 to acknowledge Internet activity - have included a definition of "advertisement" that is similar to the following:

- "Advertisement" means a notice that is broadcast or published to the general public or specific market segments about your goods, products or services for the purpose of attracting customers or supporters. For the purposes of this definition:

- a. Notices that are published include material placed on the Internet or on similar electronic means of communication; and

- b. Regarding web sites, only that part of a web site that is about your goods, products or services for the purposes of attracting customers or supporters is considered an advertisement

Court Views of "Advertisement"

Some courts have broadly construed the definition of advertisement, and policyholders have successfully argued that product packaging and point of sale retail displays qualify as “advertisements.” In E.S.Y., Inc. v. Scottsdale Ins. Co., 139 F. Supp. 3d 1341, 1355 (S.D. Fla. 2015), a competitor sued the insured, alleging it sold clothes with infringing designs and labels on the clothes and its hang tags. The court held that a "hang tag" constituted an "advertisement" such that the insurer owed a duty to defend. The court reasoned that the "hang tag" was not part of the product itself, and "had the additional function of attracting consumers to the garments themselves and to the brand more generally." The court further explained:

By way of contrast, as one knows from common experience, many products do not have fanciful hang tags and instead have, for example, a plain white tag tucked away inside them or, even more basically, a small price tag sticker stuck on the base of the product or on some other area the consumer does not readily notice. These types of labels, which likewise are not part of the products themselves, are hidden from the consumer's eye lest they detract from the product’s appeal. The hang tags here presumably did the opposite - they attracted the consumer. Defendant argues the Exist Complaint had no allegations the hang tags were used to attract customers or were sufficiently exposed to the public. Fairly read, however, the Exist Complaint made those allegations. Of course, the hang tags were not detached from the product in the way a billboard or magazine advertisement is, but the broad definition of "advertisement" in the Policy governs. If the hang tags did not clearly fit within this category, the definition at least is ambiguous with respect to the question of the hang tags.

Other courts have found that an "advertisement" can include a "retail product display," i.e., "placards exhibited above the markers with an enlarged picture" of the product1 and product packaging.2

In Mid-Continent Cas. Co. v. Kipp Flores Architects, LLC, 602 Fed. Appx. 985, 992-93 (5th Cir. 2015) (Texas law), the court held that a model house was an "advertisement." The court explained that “notice” means the "art of imparting information" or "something which imparts information" and publish means "to make public or generally known" or "to make generally accessible or available for acceptance or use." The court also emphasized that the model homes were the builder's primary means of marketing its business, and there was no evidence that customers saw any marketing materials other than the houses themselves. Thus, the court reasoned that a model house may constitute an "advertisement" under a definition similar to what is quoted above.

Under this logic, one could imagine a policyholder arguing that a knockoff is always an "advertisement." After all, retailers show products to customers in an attempt to close a sale. However, the Second Circuit recently rejected this argument in United States Fidelity & Guaranty Co. v. Fendi Adele S.R.L., 823 F.3d 146, 148-52 (2d Cir. 2016) (applying New York law). In Fendi, the claimant alleged the insured infringed upon its trademarks by selling handbags that bore the claimant's brand and logo. The court reasoned that a product brand and logo used for product identification are not advertisements, and the insured would not reasonably expect to be indemnified for disgorgement of profits made from selling goods that bore a false designation of origin.

Fendi establishes at least some limitation as to the breadth of the definition of "advertisement." It seems well-recognized that a product is not its own "advertisement," and a claim for the sale of infringing goods should not trigger "advertising injury" coverage. The court in E.S.Y. emphasized that the "hang tag" was not a part of the product itself, and the court in Fendi directly rejected the argument that a brand incorporated into a product was an advertisement. However, there are circumstances in which the line between product and advertisement, broadly construed, begin to blur. The expansive interpretations of "advertisement" adopted by other courts highlight the importance of carefully examining the pleadings and applicable state law when evaluating intellectual property claims.

The Causation Requirement

Intellectual property claims often involve allegations of advertisement and sale of infringing goods. CGL policies limit coverage to damage because of “advertising injury” and typically include an intellectual property exclusion that includes language similar to the following:

"Personal and advertising injury" arising out of the infringement of copyright, patent, trademark, trade secret or other intellectual property rights.

However, this exclusion does not apply to infringement, in your "advertisement", of copyright, trade dress or slogan.

Insurers have a reasonable argument that this exclusion, combined with the policy's limitation of coverage to damages "because of 'advertising injury'," is intended to draw a distinction between advertising of infringing goods, which may be covered, and sale of infringing goods, which is not. As a practical matter, insurers may argue that while damage caused by efforts to confuse consumers may fairly be attributed to advertising activities, damages for lost profits are not and should be excluded.

Courts hold that there is no "advertising injury" unless there is a causal connection between the offensive advertisement and the alleged damages. However, at the duty to defend stage, a court is less likely to hold that an insurer will not owe coverage for a claim that involves advertising and sale of infringing goods, on the basis that the advertisements did not cause any damages. Further, some courts have apparently assumed that the existence of an infringing advertisement at the point of sale satisfied the requirement of a causal connection between advertisement and damages.

Nevertheless, the mere existence of an advertisement should not necessarily satisfy this requirement. As the court explained in Hartford Cas. Ins. Co. v. EEE Business, Inc.,3 "a claim of patent infringement does not 'occur in the course...of advertising activities' within the meaning of the policy even though the insured advertises the infringing product…" Insurers have a reasonable argument that the policyholder should bear the burden of establishing this prerequisite to coverage, and that a claim for lost profits or other damage that is directly attributable to sale of infringing goods falls within the intellectual property exclusion.

Prior Publication Exclusion

CGL policies typically include "prior publication" exclusions, which apply to advertising injury "arising out of oral or written publication, in any manner, of material whose first publication took place before the beginning of the policy period." Several courts have held that in intellectual property claims, the term "material" as it is used in that exclusion means the claimant's protected intellectual property interest. Therefore, the exclusion should bar coverage if all of the claimant's intellectual property interests were infringed before the policy period for a claim even if the insured publishes new advertisements during the policy period.

Courts have generally held that an advertisement during the policy period will be excluded if it is "substantially similar" to prepolicy advertisements."4 In recent cases, two federal circuit courts of appeals provided some clarity as to how this exclusion applies. Both cases involved allegations of trademark infringement. In Street Surfing, the claimant alleged that the insured infringed upon the claimant’s registered trademark "Streetsurfer" in the insured's use of the name "Street Surfing" and a logo in the advertisement and sale of skateboards. In Urban Outfitters, the claimant sued the insured arising out of its unauthorized use of "Navaho" and "Navajo" names and marks in the advertisement and sale of retail clothing.5

In both cases, the court held that prior publication exclusion barred coverage, including new advertisements first made during the policy period, because the insured published advertisements that allegedly infringed on the trademarks prior to the policy period. In Street Surfing, the court explained that "if Street Surfing's post-coverage publications were wrongful, that would be so for the same reason its pre-coverage advertisement was allegedly wrongful: they used Noll's advertising idea in an advertisement" and the post-coverage publications did not include "new matter." In Urban Outfitters, the court distinguished between new advertisements with "fresh wrongs" and "mere variations on a theme," which serve "common, clearly identifiable objectives." The prior publication exclusion applies where the pre-policy advertisements "share a common objective with those that follow."

Street Surfing and Urban Outfitters are likely to bring some predictability to the application of the prior publication exclusion in intellectual property cases. If the insured allegedly infringed upon the copyright, trademark, trade dress, etc. before the policy period, any infringement of the same intellectual property interest during the policy period is excluded even if the new advertisement is not identical to the pre-policy advertisements.

This article does not address all coverage defenses that may limit or eliminate coverage for claims arising out of "knockoff" goods or alleged intellectual property violations. Many CGL policies include exclusions that bar coverage for knowing conduct on the part of the insured, certain contractual claims, and certain types of false advertising. Nevertheless, an analysis of the issues discussed herein - whether there is an "advertisement," whether the advertisement causes damage and whether the advertisement falls within the period of coverage - will often determine if there is any coverage for such a claim or not.

Download PDF Version for Endnotes

We extend our sincere thanks to Tressler LLP for providing this article to Gen Re.

About the Authors

Jim Pinderski, Partner, is an accomplished litigator whofocuses his practice in the areas of insurance coverage litigation and complex commercial litigation. He has handled a wide variety of insurance-related disputes, including issues of general coverage, environmental coverage, advertising injury/personal injury coverage, asbestos coverage, property insurance coverage, professional liability coverage and bad faith. Jim has served as national coverage counsel for several major insurance companies. You can contact Jim at the Tressler Chicago office at jpinderski@tresslerllp.com or 312 627 4092.

Michael DiSantis, Partner, focuses his practice in the areas of insurance coverage analysis and insurance coverage litigation. He represents insurance companies in litigation matters nationwide and advises insurers in non-litigated disputes, including those involving bodily injury, property damage and personal and advertising injury coverage and bad faith. You can reach Michael in the Pittsburgh office at mdisantis@tresslerllp.com or 412 925 1571.

Tressler LLP is headquartered in Chicago. With seven offices located in five states, Tressler LLP is a national law firm comprised primarily of attorneys who devote their practices to the representation of the insurance industry in coverage analysis and resolution, litigation, underwriting consultation, product development, claims management and reinsurance. www.tresslerllp.com.