-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Trending Topics

Publication

Engineered Stone – A Real Emergence of Silicosis

Publication

Use of Artificial Intelligence in Fire Protection and Property Insurance – Opportunities and Challenges

Publication

Generative Artificial Intelligence and Its Implications for Weather and Climate Risk Management in Insurance

Publication

Public Administrations’ Liability – Jurisprudential Evolution, Insurance Implications, and a Comparative Analysis Across Countries

Publication

Risk Management Review 2025

Publication

Who’s Really Behind That Lawsuit? – Claims Handling Challenges From Third-Party Litigation Funding -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Training & Education

Publication

AI Agent Potential – How Orchestration and Contextual Foundations Can Reshape (Re)Insurance Workflows

Publication

Diabetes and Critical Illness Insurance – Bridging the Protection Gap

Publication

Group Medical EOI Underwriting – Snapshot of U.S. Benchmark Survey

Publication

Why HIV Progress Matters

Publication

Dying Gracefully – Legal, Ethical, and Insurance Perspectives on Medical Assistance in Dying Moving The Dial On Mental Health

Moving The Dial On Mental Health -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

Behavioural Economics – Is It Just Another Fad?

August 01, 2017

Clio Lawrence

English

Español

Behavioural Economics (BE) has enjoyed increasing attention and application since Daniel Kahneman was awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 2002 for his work on behavior under uncertainty, especially regarding human judgment and decision-making.1 The term BE has been widely used but has seen some resistance from psychologists, arguing that in many cases the term BE is being used to explain actions and biases that are essentially psychology but presented as economics.2 The question is then when are we applying BE principles and when are we applying psychology? And outside of marketing, is any of it really effective?

Irrespective of the debate, there is no doubt it is a hot topic and has been for some time. The application of BE principles has been most obviously seen in the marketing industry, with some criticism that it has been used to manipulate consumers or that it is a fad. Regardless of your opinion of BE and its place in the finance industry, it is being taken seriously. In the UK, the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries set up a Behavioural Finance Working Party to analyse the behavioural biases of actuaries,3 and the Financial Conduct Authority banned opt-out selling and set in place rules regarding selling add-on products following a market study, which revealed that competition was not sufficiently effective.4,5

Some companies have created positions for BE specialists, and some have even set up Behavioural Economics task groups. With all this activity around BE, we naturally found ourselves asking whether BE theory has relevance in Income Protection (IP) claim management.

BE theory asserts that individuals make irrational decisions as a result of cognitive biases, even though they try not to.6 Dan Ariely coined the term “predictably irrational”,7 which describes how people are not actually as rational as they think they are when it comes to making decisions – so much so that it’s predictable. In the context of protection insurance, and specifically income protection, we are trying to better understand why people make certain decisions and are looking to BE for possible answers and tools.

Income Protection and Behavioral Economics

Income Protection, while still a small market relative to life and CI, is a fast growing one. The latest Protection Pulse reported a 17% increase in IP sales in 2016 compared to a 1.5% increase in life insurance sales and 5.2% increase in CI sales for the same period.8 The ABI also reported an increase in the number of IP policies in force in 2016, with a record payment of £3.6 billion in IP claims being paid out in 2015.9 This has largely been attributed to increased awareness around the value of IP in the market but one has to also acknowledge the context in which this increase has occurred.

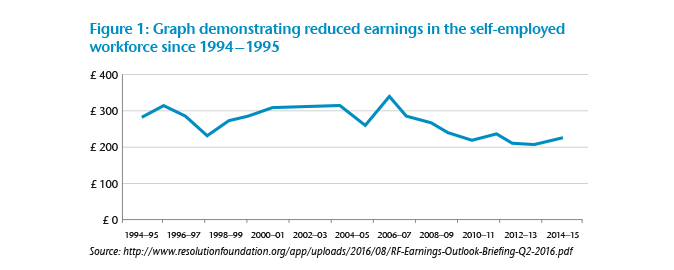

The UK has seen a steady increase in self-employment, with the Office of National Statistics reporting an increase from 3.8 million to 4.6 million self-employed people from 2008 through 2015.10 A closer look at this trend in a study conducted by the Resolution Foundation showed that despite significant growth in self-employment since the 2001-2002 period, self-employed workers’ average wages were lower in 2015-2016 period than they were in 1994-1995 (refer to Figure 1).11 The reasons for this were attributed to a reduced number of working hours, as well as the “gig economy”, where the self-employed person performs a variety a jobs rather than specializing or running his or her own business.12 This often means less job security, inconsistent hours and unstable income, and in many cases no business to return to after a period of absence. With many self-employed individuals wisely taking out IP to protect their income and business should they become unfit to work, understanding the difference in entrepreneurial vs. “gig economy” self-employment is valuable in understanding policyholders at claim stage. It is therefore essential that we endeavor to understand this group of customers so that our policies and processes are appropriate and effective; BE can be of value in this.

The Model of Human Occupation

The Model of Human Occupation (MOHO) is popular amongst Occupational Therapists as a frame of reference for understanding an individual’s motivation.13 The model theorizes humans are comprised of three interacting parts – volition (motivation), habituation (patterns and routines) and performance capacity (mental and physical abilities). Impairment or disruption in one sphere has an impact on the other two and, as a result, on the individual’s overall performance. In the context of IP claims involving a physical or mental impairment (acute or permanent), an individual’s routines and motivation are affected. As a result, when a recovery from the impairment has been achieved, there may be residual impairment in the other spheres due to this disruption. This balance may rectify proportionately with an increase in performance capacity; however, it also may not do so, and then intervention or support could be required to restore the three spheres to a state of balance. The MOHO provides us with a framework through which to understand humans and their relationship to occupation, which in turn enables us to use BE principles effectively for mutual benefit.

BE principles

In IP claims, we noticed anecdotally that increasing numbers of claimants were staying off work: i) longer than expected for their condition, and ii) after an appropriate level of recovery, or maximum medical improvement, was achieved. We specifically looked at acute conditions with established treatment protocols and predictable recovery times – not psychiatric or life-changing conditions, such as cancer. IP policies have maximum sum assured of 75% of earnings. The intention of this limitation is to create an incentive for return to work when recovered but to still provide appropriate financial support while an individual is unable to work. We noted, however, that despite being financially worse off while in receipt of the benefit, claimants were still demonstrating a hesitance to return to work (partial or full time), often resulting in conflict and dissatisfaction between the claimant and the insurer. We’ve therefore been looking at trends amongst IP claims, with the view to better understanding the behavior we’re seeing through the principles of BE. The questions we asked were:

- Do BE principles have relevance to the claims management process?

- Can we use BE principles to improve engagement in return to work (RTW) and rehab programmes?

- Can we use BE principles to improve customer satisfaction?

In order to try answer these questions, we’ve been looking specifically at the following BE principles:

- Anchoring

- Framing

- Loss aversion

- Reciprocation

Anchoring

The anchoring effect is where initial exposure to a number acts as a reference point for judgment of other values.14 Claimants are often entering the claims conversation having already been off work for some time and with firmly established anchors regarding the severity of their condition, treatment expectations and prognosis. Specific to the Life/Health claims context, these anchors may be established by health professionals that the claimants have consulted, or even friends and family who have experienced a similar condition. As people increasingly begin to take more control over their health with self-monitoring technology, wearables and general increased access to information, this anchoring can also be generated by the individual claimant. However, the accuracy of these anchors can be variable, and as many claims assessors will confirm, sometimes the medical scenario does not fit neatly within the context of the insurance contract.

Using recognized guidelines for recovery in acute injuries, we started applying the principle of anchoring to early communication with claimants – an attempt to manage their expectations with regard to the timeline of their injury, and in some cases admit the claim with no review. The intention of this was also to provide accurate anchoring information early on in the claims process to reduce repeated contact with the claimant and the potential for frustration later. Claimants were advised of the average recovery time for their condition in the context of their occupation, assuming treatment was prompt and successful. At the beginning of the claims assessment process, claimants were advised not only about recovery time but about what support would be available when the time came for them to return to work, such as proportionate benefits and rehabilitation benefits.

It should be noted that at no point would the generic recovery guideline override medical advice provided by the treating doctor. The initial conversation about the anticipated length of the claimant’s recovery is expected to reduce uncertainty, provide a guaranteed minimum period of payment and reduce the need for assessor contact in the initial period. For cases where the average recovery time is sufficient, the claims can be processed efficiently and claimants are able to focus on their recovery with minimal contact with the insurer. Early analysis of data is showing that up to 45% of claims managed in this way are not running over the average recovery time, reducing the need for intensive reviews and assessor involvement. While the research is still in its early stages, the data so far is encouraging.

Framing

The framing effect refers to how choices can be presented as a loss or a gain by bringing attention to either the positive or negative aspects of the same decision.15 As recent market studies have shown, the IP market in the UK is growing, and as a result diverse products addressing a variety of needs are being introduced. There is a demand for innovative and comprehensive products, with practical features to support claimants. For example, a UK insurer has recently launched a “Mutual Benefits” app, which provides all members with a set number of points annually that they can “spend” on healthcare services, such as GP consultations or counselling.16 Customers then have the freedom to use these benefits as they feel appropriate and can access the services directly rather than via the insurer.

Despite these features, many claims assessors still find that facilitating successful return to work with claimants can be a long and difficult process. Using the BE principles of anchoring and framing, simple and small changes have been tested in early and ongoing communication; these include highlighting policy features from initial contact rather than when they become relevant, signposting claimants to appropriate resources, and using social proofing or norms to effectively frame expectations of the claims process and even anchor an individual to the prospect of a successful and supported return to work in the near future. While framing is a difficult effect to quantify, customer satisfaction levels are anticipated to capture its effect. While this has not yet been formally measured, the informal feedback at this point suggests that the above approach is effective in improving customer satisfaction.

Loss Aversion

When used effectively, anchoring and framing are potentially very effective in combating loss aversion. Loss aversion is seen in the human tendency to be more likely to avoid loss and seek to maintain the status quo, even when the potential for gain is significant.17 It is based on the belief that the pain of losing is psychologically much more powerful than the pleasure of gain. In the claims context, loss aversion has been identified as potentially one of the most significant barriers to successful return to work.

If we prefer to maintain the status quo rather than risk losing what we have, then we may face difficulties in facilitating return to work due to social and workplace factors that create uncertainty; for example, those working in the “gig economy”. This can be seen in longer running claims where the claimant demonstrates ambivalence around RTW and rehabilitation programmes, despite improvement in their medical condition. We should, however, be mindful of not oversimplifying such scenarios and be aware of less obvious factors influencing the claimant’s approach to return to work, such as loss of confidence, embarrassment and fear of not succeeding.

While our products may have all the features necessary to facilitate a successful return to work, these alone are unlikely to quell ambivalence about return to work if there are other influencing factors. As the MOHO framework demonstrates, success at one‘s occupation is the outcome of interrelated spheres and if we as insurers understand the source of a behaviour, we will be better equipped to respond to claimants‘ needs effectively.

Reciprocity

Reciprocity is our tendency to respond to an action with an equivalent action and is a social norm, which can be both positive and negative for all parties involved.18 It comes as no surprise that when an individual finds himself or herself in a collaborative environment, the individual is more likely to reciprocate with collaboration, creating the potential for constructive goal-oriented relationships. For example, through funding rehabilitation or treatment, where appropriate, we can enter into a reciprocal relationship with the individual to create the foundation for a collaborative relationship. Another approach has been to increase the use of telephone calls both at initial assessment and at review stage, prior to making potentially inappropriate or ill-timed requests for evidence. Aside from making communication more personal, this approach has a direct impact on the speed with which information is gathered and ensures that the correct information is requested and received, creating a smoother claims experience for the customer.

Conclusion

As the IP market grows and the workplace continues to change, we shouldn’t ignore the value BE can add to our understanding of our client base. It can provide insights that enable us to better understand our claims experience, as well as drive innovation. While BE is not a tool to control behavior or achieve a cookie cutter outcome, recognizing the potential significance of these principles and behaviours in interactions enables us to better understand the influences underpinning the behavior we see. BE theory therefore can add value to the ongoing development of our processes and products – to the benefit of both the provider and the consumer.

The questions posed at the start were whether BE theory has relevance to claim management, whether BE principles can improve return to work and rehab outcomes, and whether BE can have an impact on customer satisfaction. While our observations and investigations are ongoing, the anecdotal evidence and feedback has so far supported a link between the application of BE principles and claims outcomes.

Is BE theory the solution to the above questions? That is unlikely; human behavior and our relationship to work is too complex for a simple solution. BE is by no means a magic wand, but the investigations so far would indicate that it also isn’t a passing fad and that there is room for its application in the IP claims context.

Download PDF version for Endnotes