-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Trending Topics

Publication

Engineered Stone – A Real Emergence of Silicosis

Publication

Use of Artificial Intelligence in Fire Protection and Property Insurance – Opportunities and Challenges

Publication

Generative Artificial Intelligence and Its Implications for Weather and Climate Risk Management in Insurance

Publication

Public Administrations’ Liability – Jurisprudential Evolution, Insurance Implications, and a Comparative Analysis Across Countries

Publication

Risk Management Review 2025

Publication

Who’s Really Behind That Lawsuit? – Claims Handling Challenges From Third-Party Litigation Funding -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Training & Education

Publication

AI Agent Potential – How Orchestration and Contextual Foundations Can Reshape (Re)Insurance Workflows

Publication

Diabetes and Critical Illness Insurance – Bridging the Protection Gap

Publication

Group Medical EOI Underwriting – Snapshot of U.S. Benchmark Survey

Publication

Why HIV Progress Matters

Publication

Dying Gracefully – Legal, Ethical, and Insurance Perspectives on Medical Assistance in Dying Moving The Dial On Mental Health

Moving The Dial On Mental Health -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

Finding Funding Solutions for Elderly Care

March 05, 2015

Sabrina Link

English

Demographic changes, in particular increasing life expectancy and decreasing fertility rates, continue to put pressure on social systems and society in respect of elder care. We live in a world where smaller and less stable family units are facing an increasing struggle to provide care for their elderly relatives. Increasingly, the traditional caregivers – for example, the daughters or daughters-in-law – are themselves engaged in long-term working careers. Finding solutions to fund the care of elderly relatives is therefore of key importance in ageing societies.

One measure of the mismatch between requirement and provision is the old-age dependency ratio. This is the ratio of the number of people aged 65 and over to the number of people aged between 15 and 64 years. It is projected to rise in the EU-28 countries from 27.48 in 2013 to 39.01 by 2030. By 2060, the old-age dependency ratio is expected to hit 50.16, which means there will be just two people of working age to support each pensioner.1 To put this in context, an analysis from the German private insurance sector projects that every second man and two-thirds of all women will require care in the years prior to death.2

Long Term Care (LTC) insurance provides cover against the risk of becoming too frail to care for oneself without physical assistance from another person even when using assistive devices. Even though the need to set aside funds for future care costs of an ageing population is evident, few governments have acted to create public funding systems, whilst the uptake of private LTC insurance policies has lagged far behind expectations in almost all markets. This article looks at some established LTC markets – Germany, Singapore, the UK and France – where government and private solutions coexist, and considers the reasons behind this apparent failure.

Germany

The German social security scheme aims to bear around half of the actual cost incurred by an individual in need of care. The level of support varies, depending on whether a cash benefit or reimbursement of care costs is required and whether care is provided at home or in a nursing home. The system is based on three “care levels”. The assessment of the level of care required takes account of the frequency and duration of the assistance required to provide for personal hygiene, feeding, mobility and housekeeping needs.

Criticism of the time criterion, the focus on physical abilities and the limited benefit amounts has led to the development of new concepts the government intends to introduce in the near future. An adjustment to the system has seen (small) levels of benefit granted to people with limited capabilities in everyday life, specifically including those with dementia but no physical care needs.

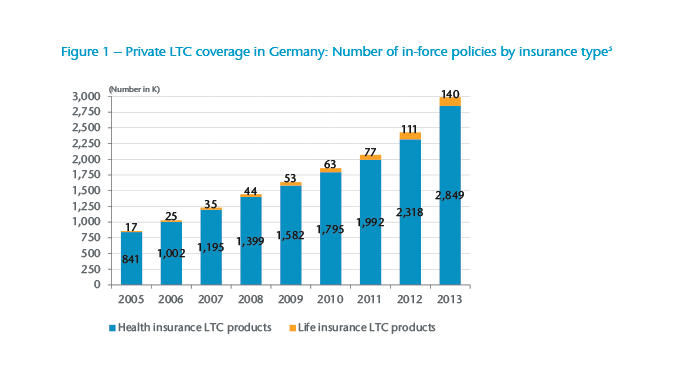

The private LTC market is characterised by competition between life and health insurers offering products that display sometimes subtle, sometimes glaring, differences. The market is dominated by the generally cheaper products that health insurers offer. However, the number of policies sold by life insurers is growing significantly, with an average annual growth of 31% in the years 2005 - 2013 compared to an average annual growth of 16% for health insurance products (see Figure 1).

The price differential between life and health LTC products is largely driven by the possibility to adjust premiums. Health insurers are obliged to review the adequacy of premiums annually and can or must adjust them if required. While policy- holders of health products are used to regular premium adjustments from their basic health insurance, life carriers must offer guaranteed premiums with only profit participation to mitigate adverse development of their portfolio. In theory premium adjustments are lawful under the terms of the Insurance Contract Act but, so far, have never been applied.4

Another reason premium levels differ is based in regulatory requirements such as the technical interest rate (health insurers use around 2.75% subject to a maximum of 3.5%, while life insurers use a maximum of 1.25% – as of 1 January 2015) or the consideration of lapses (allowed for health insurers but not for life insurers).

Standalone LTC products tend to reflect the care definitions used in the public scheme with an additional benefit trigger based on Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) and an independent dementia trigger. Benefits are paid out when either the public scheme definition is met or a certain number of ADLs is failed or the person has dementia. The benefits are tiered with reduced amounts paid at lower needs (care levels I and II) and 100% paid out for the highest needs (care level III). The benefit paid for dementia usually matches care level II. Benefits are fixed annuities, paid until death, sometimes combined with an optional additional lump sum benefit at the start of impairment.

Various premium payment structures exist, the most common being with lifetime regular premiums and limited premiums until age 85. Other product features include indexation, increased options in the event of specified changes in living conditions and without further medical evidence, and refund of premiums if death occurs before any care is given. Deferment periods – the time between sickness inception date and the beginning of benefit payments – have not found favour with distributors or customers. Applicants are typically medically underwritten, allowing policies to operate without a waiting period – the time between commencement date and the beginning of insurance cover. A new product offered by health insurers, and subsidised by government, is different in that no underwriting is allowed, there is an obligation to contract (except for those who are already in need of care) and all applicants are subject to a waiting period of five years.

Perhaps because carriers struggle to sell adequate volumes, other LTC product formats have appeared on the market. A recent trend is to combine LTC with disability income or annuity insurance. The underlying (disability income or annuity) policy provides an increased (e.g. double) benefit if the claimant is in need of care at the same time. Alternatively, purchasers of life and disability cover are offered the option to add LTC insurance at a later date without undergoing further underwriting.

In Germany LTC insurance is perceived as expensive and is not widely distributed yet relative to the population size. It is possible that the new product approaches may help to penetrate the market more.

Singapore

Singapore operates the Central Provident Fund (CPF), a mandatory social security savings plan for the working population. CPF policies cover savings for retirement, housing and healthcare, with LTC a subsection under saving for healthcare. The Singapore model serves as an example of a public-private LTC partnership. The government’s stated aims include nurturing a healthy nation, promoting personal responsibility for health and healthcare financing while providing good and affordable medical services. There is a reliance on market forces to improve these services, but the system allows for intervention when market forces fail to keep costs down. The solution to the cost of caring for Singapore’s senior citizens is ElderShield, an insurance scheme set up in 2002 and run by the Ministry of Health (MoH).

ElderShield initially operated using two life insurance companies chosen by a tender process, with a third company added five years later. The MoH provides the framework for the scheme while the private insurance industry assumes the role of risk taker and administrator. Pricing was based on overseas data in lieu of local experience. At launch the monthly benefit was S$300 payable for a maximum of 60 months per lifetime. This was later increased to S$400 for a maximum of 72 months for new entrants. Existing policyholders were given the option to upgrade their policies to these enhanced benefit conditions. A further review of benefit levels, scheduled for 2012, has been put on hold due to the government’s efforts to focus on extending the MediShield scheme (a public-private health insurance partnership) during this same period.

Singapore nationals and all permanent residents aged 40 to 69 holding CPF accounts were automatically enrolled in the scheme. There is a right to opt out and no underwriting except when opting back in. Individuals are randomly allocated to one of the three insurers. People already in need of care can apply for benefits through a separate scheme. Premiums are payable to age 66 and are deducted from individual’s MediSave accounts – funds that cover personal and family healthcare costs including outpatient treatment and long-term medication.

Premium adjustment is subject to independent investigation and MoH approval. Adjustment is possible only at five-year intervals and is limited to 20% of the current price. Premium rebates are considered every five years to account for better than projected experience. The government resolved to return 50% of any accumulated surplus to existing policyholders. In 2007 and 2012 policyholders were entitled to rebates, as actual claims were lower than projected.5

The MoH has the final call on claim validity if the involved parties cannot agree. Care benefits are payable when three out of six ADLs are failed following a deferred period of 90 days. Nursing home charges in Singapore are estimated to range between S$1,200 and S$3,500 per month.6 As ElderShield provides for only basic levels of care, a MediSave account may be used to finance approved top-up plans sold by the three participating insurance companies up to a cap of S$600 per insured person per year. With supplements monthly benefits can reach S$3,500 and be extended throughout life. Some of the supplements include initial lump sum benefits, death benefits during the claims period or dependent care benefits if the claimant has a child.7

By year-end 2012, more than one million citizens (out of the 3.1 million with MediSave accounts) had an ElderShield policy, while 265,000 people had a policy with supplementary cover.8 The opt- out rate decreased significantly from 38% initially to 8% for the 2011 cohort.9 Managing the care costs of those opting out may pose a political and economic challenge in the future, but at least the vast majority of the population enjoys some basic protection.

United Kingdom

Political devolution has allowed the four UK nations some freedom to pursue differing LTC strategies; for example, only Scotland provides free personal and nursing care services.10 The actions of the UK government in respect to England, of the Scottish Executive and of the National Assembly of Wales, however, have failed to quell concerns about the fairness, efficiency and sustainability of care arrangements.

Nationally, the UK health system is financed by the government with individuals of working age contributing to the cost through their national insurance contributions. The system provides elderly or disabled persons and their caregivers with cash help and other benefits, such as home adaptations and special equipment. Care is provided by a blend of voluntary organisations, local councils, health authorities and private agencies. A high proportion of older adults are helped by friends or family and pay for their own care.

Although there is no precise definition of LTC used in the UK, increasingly sophisticated assessments of health and social care needs are employed to understand the requirements of a given individual. This divide between health and social care, a subject for much discussion, means that direct comparison with other schemes can be difficult. Healthcare is not means tested and free at the point of delivery, whilst social care is means tested in England and Wales, with individuals paying all their care costs until their assets have dwindled below £23,250.

Private, pre-funded LTC insurance policies have not been sold since 2004. All the care products currently available are immediate needs annuities (INAs) – plans that provide a guaranteed, tax-free income to meet the costs of the insured’s registered care provider. The annuity starts immediately and continues until death. It is financed by a single premium based on age and state of health. Some products return a percentage of the capital invested if death occurs within the first six months.

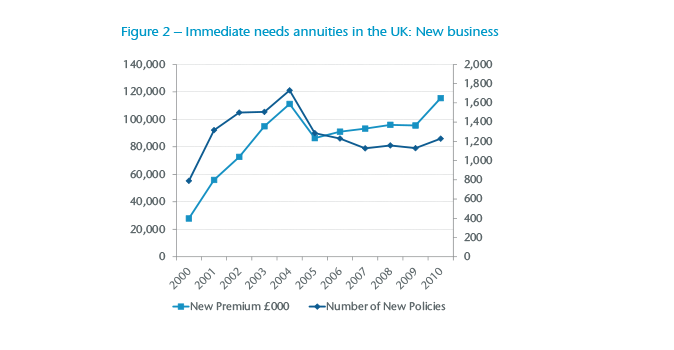

There are currently three providers of INAs in the market. To date the uptake of INAs has been slow and largely by wealthy, single people. In the peak year for sales (2004), the number of new policies issued totalled 1,730 but in 2010 this sank to 1,288 (see Figure 2). Yet, due to the high single premiums involved, the premium volume hit £127 million in 2012. Naturally, INAs are focused at higher age bands, with 99% of the products held by people aged above 70. Overall, the number of policies in force comprising pre-funded products, INAs, deferred needs annuities and LTC bonds totalled 30,515 in 2012 (of which 5,753 were INAs) compared to 46,104 in the peak year 2003. Between 2010 and 2012, an average of £108 million per year was paid in claims.11

The market for INAs may still be very small but it has the potential to grow. In 2012 around 43% (175,000) of older care home residents paid the full costs of their LTC.12 This is because their assets had not yet fallen below the threshold set in the public scheme. It is estimated that as many as 40% of those self-funders can afford, and would benefit from, an INA.13

The government-appointed Commission on Funding of Care and Support was critical of the shortcomings of the system of funding adult care in England.14 The main recommendations for reform that it made were subsequently codified in the Care Act (2014) and will apply from April 2016:

- Individuals’ lifetime contribution towards their personal social care costs is capped at £72,000.

- After the cap is reached, individuals are eligible for full state support.

- The means-tested threshold in assets increases to £118,000.

- Eligibility criteria for service entitlement are standardised to improve consistency and fairness across England.

It is important to remember that the changes will apply only in England. The cap applies only to the “personal social care” element and is subject to both eligibility criteria and the prevailing local authority rate. The cap will not cover general living expenses (estimated at £7,000 - £10,000 per year), or any “hotel” costs above the rate paid for by a local authority. Time will tell whether or not a new private market for LTC will develop subsequently to support this new funding structure.

France

In the public sector, the costs of home care and nursing care are paid for through a mixture of state payments and public health insurance. The state covers the dependency part of the care (help to perform ADLs) via the allocation personalisée d’autonomie – the personalised autonomy allowance, or APA – and for the nursing part of the care (nursing and medical care) via health insurance. APA is co-funded by the National Solidarity Fund for Autonomy (CNSA), which is a centralised body responsible for funding support services for people who are no longer independent. Its funds come from employer social insurance contributions and taxation including a “general solidarity contribution”.

For those living at home, APA provides support towards expenses incurred in line with a personalized support plan identified by a social-medical team. Plans generally include support for both ADL and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) by employing a caregiver who could be a family member although not the spouse or the partner. For those living in a retirement centre, APA offsets a portion of the dependence cost while the remainder is paid by the resident.

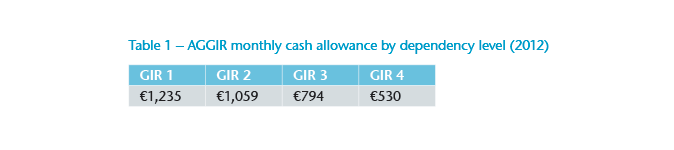

Care is classified according to a national scale gérontologique known as AGGIR (Autonomie Gérontologie Groupes Iso-Ressources) that defines six levels of dependence from independent (GIR6) to very dependent (GIR1). Only the first four levels open entitlement to an allowance. The amount of APA received depends on the assessed level of dependence (GIR) and the applicant’s monthly income (up to a 90% reduction). The monthly cash allowance is limited to national ceilings (see Table 1).

Evaluation includes 10 “discriminatory” variables that are used for calculating the GIR, and seven “illustrative” variables that provide useful information for elaborating a support plan:

- Discriminatory variables: Coherence, Orientation, Toileting, Dressing, Eating, Continence, Transferring, Indoor/Outdoor movement and Telephone communication

- Illustrative variables: Financial Affairs, Cooking, Housekeeping, Transportation, Shopping, Medical treatment and Leisure activities

France has been a leading market for private LTC insurance for over 30 years. Almost six million people are covered by insurance companies, mutual insurance companies and provision funds.15 This number represents around 15% of the population aged over 40 years. The average entry age is 60 years and the average age when a person becomes dependent is 79 years.16 Benefits are usually monthly fixed annuities not earmarked for care.

Providers attach great importance to providing “assistance benefits”, such as advice on how to retain autonomy, find a care home and organise domestic care services, as well as proposing psychological support. The products on the market usually contain a waiting period between one (for other diseases than dementia) and three years (for dementia) except for accidents. If a claim occurs during that period, the policyholder is not entitled to a benefit, premiums paid will be reimbursed and the contract is terminated.17 A deferment period of 90 days is commonly included.

The group market is large; almost half of all LTC policies are group business. Employers may pay a share of the premium and employees are generally required to participate in the plan. However, a lot of group plans provide only temporary annual coverage and employees lose their coverage when they are no longer working.18

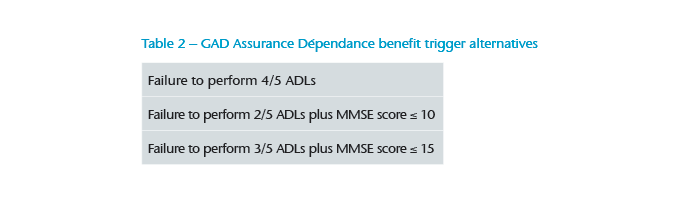

The private LTC market is characterised by a jungle of definitions, including some based on the AGGIR scale and others using an ADL measure. The Fédération Française des Sociétés d’Assurances launched the new label “GAD Assurance Dépendance” in May 2013 with the aim to create a common technical base for insurance contracts that cover total LTC. Features of this “label” include no medical underwriting below age 50, a minimum benefit of €500 per month to be paid as an annuity until death, and a common trigger based on ADLs (dressing, mobility, washing/continence, feeding and transferring) with cognitive assessment based on Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores. The benefit trigger itself consists of three alternatives (see Table 2).

Benefits from total impairment are hence based on a common set of alternative triggers, but for partial impairment, which pays 50% to 60% of the benefit, there are several definitions on the market. They are based on the five ADLs, MMSE score or on the AGGIR scale. Around two-thirds of covered people (68%) have opted to cover only total dependency.19

France is one of the leading markets for LTC insurance, with long experience both in the public and private sector. The focus on the better age groups by the insurance companies and financial strains on the public system suggest this is a market with potential to grow.

LTC in a nutshell

An internationally recognised, and widely used, definition for LTC insurance is based on six Activities of Daily Living (ADLs): dressing, feeding, washing, continence, mobility and transferring. Here “transferring” means the ability to get into an upright position from a bed or a chair; “feeding” does not include the ability to prepare meals.

To claim, the insured person must be incapable of performing a defined number of ADLs even when using special equipment. Instead, they require continuous physical assistance from another person and are very likely to require help for the next six months. This means, for example, that a person who can use a wheelchair to move from one room to another will not fail the ADL “mobility”.

Gen Re LTC claims experience shows “washing”, “dressing” and “mobility” are the first ADLs to be failed and “transferring” and “feeding” the last. For practical reasons, if a public scheme exists, private insurance products often copy the local definition, sometimes in addition to the ADL trigger.

People suffering from dementia also require help and support, but they may remain physically capable of performing ADLs so would not qualify for benefit based on ADL assessment alone. For this reason, many products consider dementia as an alternative claims trigger based on the individual’s need for continuous supervision by another person. Different tests are used to measure the severity of dementia in this context. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) and the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) are popular. The MMSE consists of questions and tests of mental ability with points allocated for correct answers. A maximum score of 30 points is possible, which indicates normal cognitive functioning.

Conclusion

The challenges of meeting the care needs of ageing societies are being approached in different ways by governments and insurance companies in different areas of the world. In some countries, Germany and France for example, a well-established public system exists that must overcome various challenges in the future, not least of which being that so many people remain to be convinced that setting aside money to fund for their future care is imperative. This is one reason why the market for private LTC products is still extremely small, especially in Germany, although political indecisiveness and unfavourable past experience make it difficult for UK insurers to launch sustainable and affordable pre-funded products. Singapore demonstrates how an effective and widely accepted public-private partnership can provide cover for almost the whole population. Nevertheless, public benefits are still too small to provide a complete solution but supplementary policies are not bought by everyone. More action is needed to tackle the rising problem of funding care, and only time will tell if any nation is fully prepared to meet the challenge.