-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Trending Topics

Publication

Engineered Stone – A Real Emergence of Silicosis

Publication

Use of Artificial Intelligence in Fire Protection and Property Insurance – Opportunities and Challenges

Publication

Generative Artificial Intelligence and Its Implications for Weather and Climate Risk Management in Insurance

Publication

Public Administrations’ Liability – Jurisprudential Evolution, Insurance Implications, and a Comparative Analysis Across Countries

Publication

Risk Management Review 2025

Publication

Who’s Really Behind That Lawsuit? – Claims Handling Challenges From Third-Party Litigation Funding -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Training & Education

Publication

AI Agent Potential – How Orchestration and Contextual Foundations Can Reshape (Re)Insurance Workflows

Publication

Diabetes and Critical Illness Insurance – Bridging the Protection Gap

Publication

Group Medical EOI Underwriting – Snapshot of U.S. Benchmark Survey

Publication

Why HIV Progress Matters

Publication

Dying Gracefully – Legal, Ethical, and Insurance Perspectives on Medical Assistance in Dying Moving The Dial On Mental Health

Moving The Dial On Mental Health -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

Should Obesity Be Considered a Disability?

December 13, 2015

Patricia Bailer

English

Despite the focus it's been given by world leaders in the medical community and government, obesity remains a global health issue. As of 2014, nearly 40% of adults worldwide (18-years-old and over) were overweight - of those, 13% were obese. 1 Unfortunately the goals set at the 2011 UN Summit to get a handle on the rising obesity rate by 2025 do not seem feasible, with rates continuing to climb each year. Obesity's impact can be seen in chronic conditions that arise as a result of it - from heart disease and stroke, to type 2 diabetes and even certain cancers. With mortality and morbidity issues that may result from these conditions, how can insurers remain vigilant when it comes to risk management, and what potential implications result if obesity becomes classified a disability?

1 WHO, 2015

Since the landmark 2014 European Court of Justice (ECJ) ruling that classified obesity as a disability, several articles have been written about it and the potential response of U.S. courts1 Even though the plaintiff in the European court case believed he could perform the duties required in his own occupation, the European Court of Justice ruled obesity can be classed as a disability.

Since the case was sent back to the Danish court for reconsideration, no decision has been rendered and one can only speculate its outcome at this time. And, although the background of the decision is labor law-related and the case reads more like the implementation of our ADA act, it begs the reader to ponder if fallout could occur. Gen Re continues to monitor this case. There are, however, U.S. court cases already dealing with this very issue: for example, Melvin Morriss, III v. BNSF Railway. Mr. Morriss claimed his potential employer reneged on a job offer because of his weight. His build was 5'10", 282 pounds when he applied for work at BNSF Railway. He asserted that he passed all required tests to become a machinist and received a conditional job offer from the company. The offer hinged on his passing a physical exam. He agreed to the physical exam, which revealed he was morbidly obese. The company's medical officer determined Mr. Morriss was not qualified for the position due to health and safety risks associated with his obesity. Thus the company rescinded the conditional offer. Of note is the fact that Mr. Moriss claimed he had no impairment limiting his ability to perform the job and did not require accommodation, and he is now urging the Eighth Circuit to revive his case.

In another case, Pennington v. Wagner's Pharmacy Inc., a management resource told the plaintiff's supervisor to fire the plaintiff because of her appearance; she was morbidly obese. The Kentucky Supreme Court ruled that simply because she was obese did not mean she was disabled.

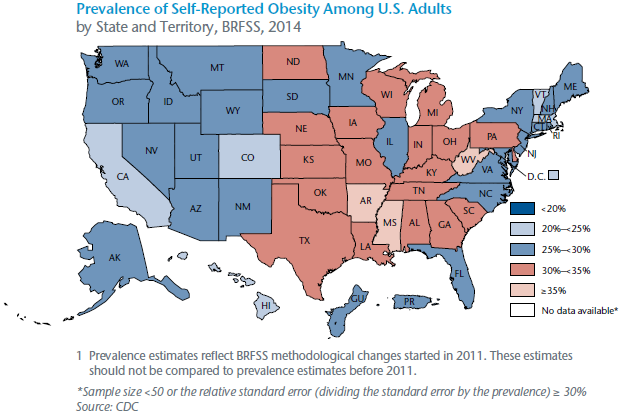

Clearly divergent views exist on whether obesity is a disease or disability, and the results of the recent SERMO survey suggest a drastic difference of opinion between survey participants in the United States and Europe. The survey polled 2,238 doctors for their opinion on whether obesity should be considered a disability.

Although a difference of opinion is at hand regarding whether obesity is a disability, it can be acknowledged that obesity is a complex interaction of genetic predisposition, social, cultural and environmental influences. Generally, we liken obesity to smoking (tobacco) use. We know smoking or use of tobacco may contribute to poor health, such as COPD, cancer, emphysema and many other conditions, and may lead to individuals becoming impaired and often times disabled per policy terms. Obesity has a similar impact on health, such as cardiovascular disease (including stroke, heart attacks, etc.), diabetes, orthopedic (joint disease), respiratory difficulties and psychosocial problems, yet obesity rates continue to increase in an overwhelming fashion and unfortunately are not isolated to any one geographical location or age bracket. The implications are significant when you consider that a child with at least one obese parent has a 50% chance of becoming obese and the chance increases to 80% if both parents are obese.

Compelling statistics from the Gallup-Healthways Well-Being Index make the argument that the impact on the U.S. appears far greater than any other country since 62.8% of all American adults are overweight or obese.2

Consistently, we hear lifestyle intervention with behavioral changes is the first line of treatment. Diet and medical intervention have historically had varying degrees of effect on obesity. A recent article in The Times suggests more than "1/5 of obesity is genetic meaning millions of obese individuals may not be able to overcome their weight problems through diet and exercise alone."3 The article references a study that analyzed DNA from people worldwide.4 It concludes, in part, that obesity may be caused by DNA rather than lifestyle. When obesity is genetic, personalized therapies and drugs may be more effective.

While exercising and eating healthy are still the best protections against becoming excessively overweight, from a claims risk management perspective it's key to understand the psychosocial impact of the disease and its corresponding impact on comorbidities. Treatment approaches - including cognitive behavioral therapy and not simply urging patients to exercise more, eat carefully or resort to gastric bands/surgeries - must be considered.

Todd Witthorne, Kevin Binham and James Guszcza's article "Tipping the Scales" reminded us of the burdens obesity exerts on the workforce, "As workers get heavier so does their impact on healthcare and workers' compensation."

Impact on Claims Management

A diagnosis alone does not guarantee the existence of functional loss that limits or prevents work. The plaintiff in the 2014 ECJ case felt his weight had no impact on his ability to perform his occupation as a nanny. Not all individuals with a BMI5 in the obese or morbidly obese category file claims (e.g., Disability, Critical Illness, LTC, waiver of premium, health/medical reimbursement or even death claims). Gaining greater insight into their motivational levels is key to the effectiveness of claims management. We believe if one has the "disability mindset" or a mindset of entitlement, claim incidence may increase and claim durations may be prolonged. If the U.S. federal government adds obesity as an automatic or compassionate allowance within the Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) program, absent any other comorbidity, claims incidence may increase. Such a development would also add stress to the solvency of the already strained disability insurance trust fund. Furthermore, changes in the healthcare insurance law and shifting priorities of employee benefits may also trigger change.

Claims management requires an understanding of the psychosocial impact and corresponding co-morbidities of obesity. It's important that carriers prepare themselves to deal with these troubling statistics from a Medicare Supplement, Disability, Critical Illness, Long Term Care and Life perspective.6 Claims risk managers may be challenged in how they evaluate these potential claims and need to be more aware of the new treatment regimens that continue to arise for those who are obese.

Policy Language

States may challenge the application of existing policy language. While the list below is not all inclusive, the following existing disability policy provisions and definitions could be tested:

- Sickness/Illness

- Appropriate care and treatment

- Reinstatement

- Total Disability

- Occupation (regular/Own Occ and Job versus Occ)

- Complications of pregnancy

- Cosmetic (elective) care

- Physician

- Pre-existing condition

- Presumptive

- Rehabilitation

- Mental/Nervous

- Contestability/Incontestability

- Recurrent/Concurrent Disability

If policy language is indeed tested, what does this mean to claims professionals? Claims risk managers may be asked to:

Heighten their awareness and understanding of conditions, social norms, medical advances and technological breakthroughs. The manner in which occupations are performed is ever changing and if claims professionals don't stay on top of the advances both from a technology and treatment perspective, claim decisions could be inaccurate and claim durations unnecessarily prolonged.

Engage risk resources in a heightened fashion. Comorbid claims require multi-disciplinary approaches to manage them (e.g., psychological vs. physical, and if a claim involves psychological mental/nervous components; does this fall under an otherwise limited benefit period or is the condition claimed organic in nature?).

Notes on U.S. Definition of Obesity

In June 2014 the American Medical Association (AMA) decided to classify obesity as a disease. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services followed suit, as did a healthy debate about whether any one gene imparts obesity since over 250 genes have been identified, and gene expression of obesity is still in the infancy stages. Obesity has been linked to damage of the mitochondria responsible for energy regulation and metabolism. Linking obesity to one's DNA supports the argument that obesity is an illness. It’s also a co-morbid condition and/ or contributing factor that may cause disability, not the only factor.

Evaluate medical evidence relied upon at the time of underwriting and time of claim, but also perhaps evolve to compare and contrast BMI classifications at appropriate intervention points and possibly at the time of reinstatement. This will alert claims professionals to apply policy provisions with heightened consistency and draw their attention to the potential of pre-existing conditions, contestability concerns, etc. It will also help to reinforce milestones achieved in the disease's progression. If the BMI decreases, how does this correlate to one's symptomatology from both a frequency and severity perspective? Again the idea is to implore the claims organization to ensure their professionals understand how to manage risk versus simply processing claims in a transactional fashion.

Shift the way appropriate care and treatment is evaluated, especially if policy language changes to better support statutory and regulatory requirements for obese individuals. Treatment notes should include addressing the causes of obesity (diet, inactivity, emotional issues, medical conditions, genetics, etc.) and exploration of varying treatment modalities (e.g., lifestyle change or medication) as a means for appropriate care and treatment to affect the direct results of obesity and the complications of the disease process. Treatment regimens of the future are multidisciplinary focused and include cognitive behavioral therapies.

Rely more on rehabilitative provisions within policies as a means to aid claimant's return-to-work efforts; otherwise, potential mandates under Employment Law may need revision (e.g., ADA).

Better understand the overall mindset of an obese individual and the corresponding effect on one's motivation to work or return to work.

Better understand fall-out from increased scrutiny on this issue that may orient employers toward being more cautious about hiring decisions.

The list could go on and on, begging claims organizations to invest in their talent management to ensure they are readying themselves for this shift.

What's Next?

How the U.S. federal government will define obesity is yet to be determined. It has been reclassified as a diagnosis. A diagnosis, in and of itself, does not speak to whether an individual is experiencing a functional loss that limits, restricts or prevents the performance of the occupation. A Danish government spokesman echoed this distinction when the EU decision was rendered, "[T]oday's judgment does not change anything and does not mean someone can claim benefits simply for being obese."7 It does, however, open the door - and potentially the flood gates - to those that interpret this differently. We need to get our arms around this topic globally, since the problem will not simply go away.

In Our View

We remain confident that claim professionals in the industry are evaluating each claim on its own unique set of circumstances. A diagnosis, in and of itself, does not speak to whether an individual is experiencing a functional loss limiting, restricting or preventing the performance of the occupation. As such, we will keep a keen eye on additional court decisions and their corresponding impact, if any, on our industry.