-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Expertise

Publication

Production of Lithium-Ion Batteries

Publication

Time to Limit the Risk of Cyber War in Property (Re)insurance

Publication

Generative Artificial Intelligence in Insurance – Three Lessons for Transformation from Past Arrivals of General-Purpose Technologies

Publication

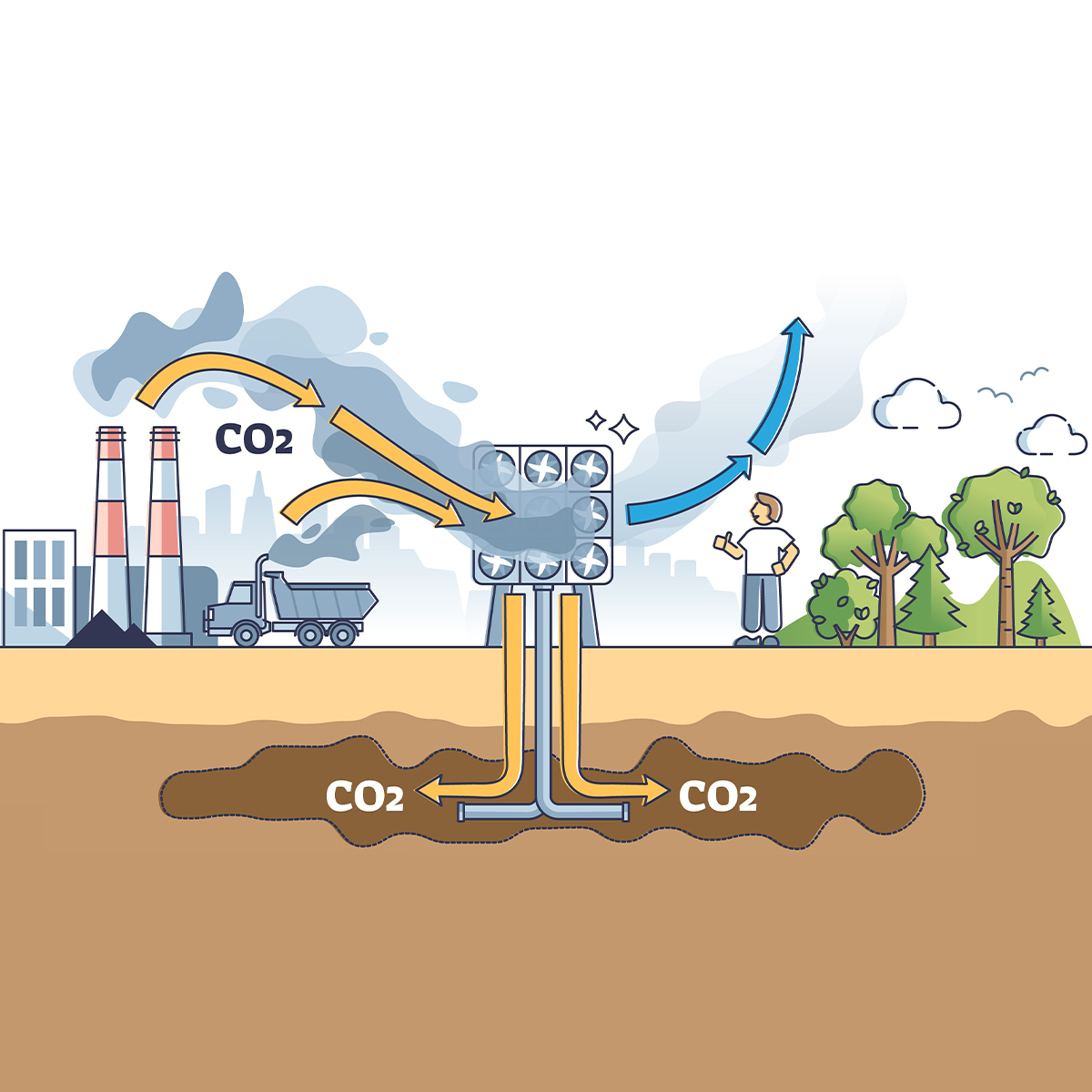

Human Activity Generates Carbon and Warms the Atmosphere. Is Human Ingenuity Part of the Solution?

Publication

Inflation – What’s Next for the Insurance Industry and the Policyholders it Serves? -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

Gen Re’s valuable insights and risk transfer solutions help clients improve their business results. With tailor-made reinsurance programs, clients can achieve their life & health risk management objectives.

UnderwritingTraining & Education

Publication

The Key Elements of Critical Illness Definitions for Mental Health Disorders

Publication

What Are We to Make of Cannabis Use in The Insured Population? Business School

Business School

Publication

Knife or Needle: Will the New Weight Loss Medication Replace Bariatric Surgery?

Publication

Weight Loss Medication of the Future – Will We Soon Live in a Society Without Obesity? Moving The Dial On Mental Health

Moving The Dial On Mental Health -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

Alzheimer’s – Is Early Detection Becoming a Reality?

February 13, 2019

Sabrina Link

English

For a long time, Alzheimer’s could only be definitively diagnosed after a patient’s death based on neuropathological findings in the brain. Positron emission tomography (PET) scanning and spinal fluid technologies can improve on purely clinical diagnosis, but their cost and a lack of any cure means they are hardly used.

New blood tests potentially represent a real step forward.1 They promise objective detection in the living years before clinical symptoms arise. Their emergence coincides with new Alzheimer’s diagnostic criteria from the National Institute on Aging (NIA) and the Alzheimer’s Association (AA) that uses biomarkers in place of cognitive signs and symptoms. This represents a shift from a syndromal approach to a biological construct.2

Alzheimer’s is a degenerative brain disease and the most common cause of dementia.3 Alzheimer’s causes problems with memory, thinking and behaviour. Symptoms typically develop gradually, worsening with time, eventually interfering with daily life to the point where an individual needs extensive supervision and support.

People with Alzheimer’s live on average eight years after symptoms become noticeable, but survival can range from four to 20 years depending on age and co-morbidities.4 Available treatments only retard the worsening of symptoms but do not offer a cure.

The overall severity of Alzheimer’s (and other dementias) can be measurable using the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) assessing not only cognitive ability but other important areas of function: memory, orientation, judgement & problem solving, community affairs, home & hobbies and personal care. Scoring 0.5 means questionable dementia while a score of 3 means severe.

The Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) is a commonly used measure of cognitive function alone. A score of 25 or more out of 30 is considered normal. Scoring 24-21 implies mild impairment, 20-10 moderate, and below 10 severe, although slightly different thresholds are in circulation as well. On average, the MMSE score of a person with Alzheimer’s will decline two to four points each year.5

The most important risk factors remain age, family history and heredity, and they cannot be changed. But evidence suggests other risk factors we can influence, for example eating a healthy diet, staying socially active, avoiding tobacco and excess alcohol, and exercising both the body and mind. Family status and poor sleep might have an impact.6

Alzheimer’s is identified by two abnormal structures that develop in the brain. Plaques – are the deposits of a protein fragment called beta-amyloid that builds up in the spaces between nerve cells, unnoticed for up to 30 years before clinical symptoms. Tangles - are the twisted fibres of another protein called tau and build up inside cells. Most aged brains have some plaques and tangles but the brains of people with Alzheimer’s are present in greater number and develop in a predictable pattern.

According to the new NIA and AA diagnostic criteria, Alzheimer’s can be diagnosed if there is evidence of significant pathological changes in both amyloid and tau proteins even without clinical symptoms. An individual with biomarker evidence of beta-amyloid deposition alone, but has normal tau biomarkers would be categorised as “Alzheimers; pathologic changes”, an early part of the ‘Alzheimer’s pathophysiologic continuum’. Tests to detect these biomarkers include brain scans with radioactive tracers or analysis of cerebro-spinal fluid taken via lumbar puncture. Symptoms would still be used for the clinical staging of individuals on the “Alzheimer’s continuum”. Having said this, the new definition is only intended to be used for research, not routine clinical care so that for the moment nothing changes for the daily practice.

Private long term care insurance products often use a separate dementia trigger alongside a benefit trigger focused on physical impairments like activities of daily living.

Although all kinds of dementia are covered, not only Alzheimer’s, the new definition will not have an impact on claims management for now. This might change once the relevant biomarkers can be ascertained routinely. This underlines the importance of a severity criterion in the definition of dementia in the contract wording. Benefits should only be payable if symptoms of moderate or even severe cognitive decline are present. Nonetheless, claims management could become more vulnerable to early claims and even legal disputes. A respective exclusion clause might help to a certain extent. On the other hand, using biomarkers could make the assessment of Alzheimer’s more objective. Another question is whether the underwriting process would have to be modified. Anti-selection might occur if people undergo screening before applying for a policy. One might want to ask the applicant whether a test has already been taken.

These issues will have to be addressed even more so once diagnostic blood tests have become mature enough for clinical routine. Three groups of scientists have recently developed and validated blood tests to detect Alzheimer’s with relatively good statistical outcomes. The blood tests detected abnormal beta-amyloid, or proteins from dead nerve cells.

Although only one of these studies suggested clinical utility might not be many years away, they have the potential to increase the speed of screening for new drug trials. By replacing expensive scanning and invasive investigations they could become invaluable in accelerating the process of developing new therapeutic strategies for Alzheimer’s.

In clinical practice the blood tests could act as an initial screening funnel to identify people who should undergo further diagnostics such as PET scanning or lumbar puncture. Understanding how the tests work in the population as a whole is an important next step; abnormal amyloid may be present in some individuals who do not have Alzheimer’s and be absent in some people who have Alzheimer’s. However, once the tests reach clinical maturity and become widely used they will be able to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease years before outward signs of cognitive decline have begun to show. This has implications for doctors attending to their patients, but also for insurance companies covering dementia and especially Alzheimer’s disease.

Endnotes

- Nakamura, A. et al., High performance plasma amyloid-β biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 554, 249-254 (2018). Nabers, A. et al., Amyloid blood biomarker detects Alzheimer’s disease. EMBO Molecular Medicine (2018). Preische, O. et al., Serum neurofilament dynamics predicts neurodegeneration and clinical progression in presymptomatic Alzheimer’s disease, Nature Medicine (2019).

- Jack, C.R. et al (2018) NIA-AA Research Framework; Towards a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 14. 535-562. https://www.alzheimersanddementia.com/article/S1552-5260(18)30072-4/fulltext.

- Alzheimer’s Association. 2018 Alzheimer’s disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2018;14(3):367-429. https://www.alzheimersanddementia.com/article/S1552-5260(18)30041-4/abstract.

- Preische, O. et al., Serum neurofilament dynamics predicts neurodegeneration and clinical progression in presymptomatic Alzheimer’s disease, Nature Medicine (2019).

- Alzheimer’s Association, https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/diagnosis/medical_tests.

- Preventing Dementia through Mid-Life Interventions. Risk Insights January 2019.